New research from our lab shows that people who are perceived to look “stereotypical” of their racial group are believed to be more meta-prejudiced. This effect makes others avoid contact with them.

Definition: How is prejudice defined in psychology?

In psychology, prejudice is typically defined as unfounded negative attitudes that people hold toward others based on the groups they seem to belong to. For instance, psychologists often study prejudice in terms of gender, race/ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, religion, or political orientation. Linguistically, the word “prejudice” is closely related to the word “pre-judgment”, as it involves negative preconceptions that people have about others.

Most people hold some prejudice toward other individuals based on their group memberships, and this can have profound consequences (Professor Keith Maddox provides a good introduction here). One consequence is that prejudice shapes whom people want to interact with and whom they avoid. For instance, prejudiced people often avoid social settings where they may meet people from other racial groups. They are also less likely to have friends from other racial backgrounds than their own. Thus, because it makes people avoid each other, prejudice can lead societies to become socially segregated.

From prejudice to meta-prejudice

However, beyond the prejudice that individuals may personally hold, there is another layer that influences whether people want contact with each other. Specifically, individuals have an expectation of how prejudiced they believe others to be toward them (so-called meta-prejudice). Unsurprisingly, if individuals believe that people from other groups are prejudiced toward them, they are less likely to want contact with these people.

This has important implications. Even if people themselves are free of personal prejudice, such expectations can continue to negatively influence their contact preferences. For instance, in the context of the U.S., which has a long history of racism and intergroup conflict, people from different racial groups may themselves have overcome their personal prejudices but still expect that others may be prejudiced toward them. Thus, this perception of meta-prejudice can still make people avoid each other.

How people infer meta-prejudice from superficial features (“stereotypical” appearance)

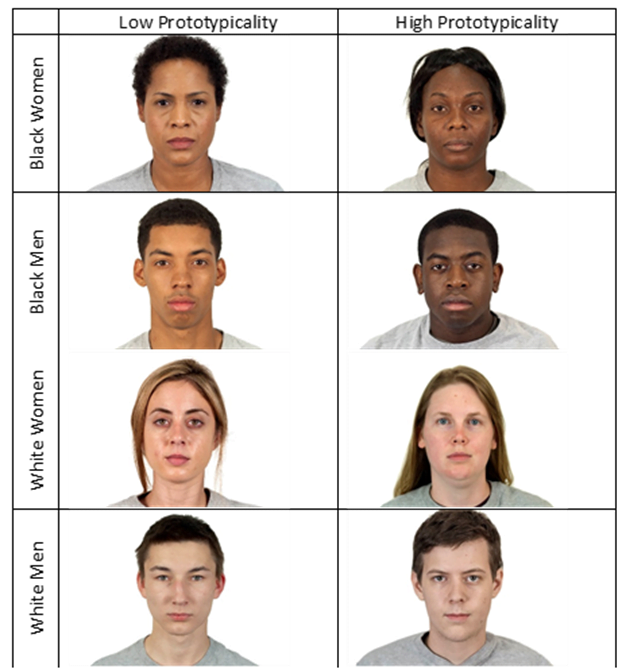

Examples of faces that by a group of raters were evaluated as low or high in prototypicality. Source: https://www.chicagofaces.org/

In a series of experiments, we now showed that whether people believe someone is prejudiced in the first place depends on how this person looks and what people associate with their appearance. In the first experiment, participants were presented with several images of people who commonly are assumed to look more or less stereotypical of their group (see image). Two factors underlying this “phenotypic prototypicality” are skin-tone and physiognomy (facial features). Our results showed that the research participants believed that prototypical-looking individuals are more prejudiced than less prototypical-looking individuals. This effect made our research participants less willing to have contact with individuals whose looks were perceived as more prototypical.

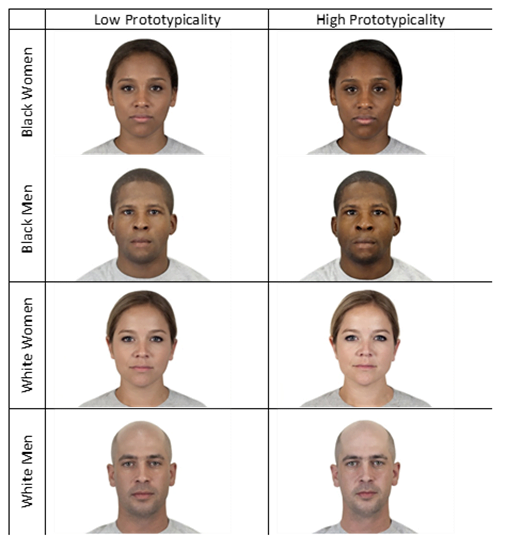

Low and high prototypicality versions of the same faces.

To replicate these results, we conducted two additional experiments. In these experiments, we altered the prototypicality of faces by slightly morphing them with a person from another racial group (see image for examples). Participants always saw only one version of the image and were asked questions about the person. Again, we find that the participants who saw the more prototypical versions of the faces thought that these individuals were more prejudiced than those who saw the less prototypical versions of the faces. Once more, this explained why participants were less willing to have contact with them.

Importantly, in each experiment, meta-prejudice (i.e., expectations that others are prejudiced) led participants to become less positive toward contact with them no matter their own prejudice or the frequency and quality of their contact with racial out-group members.

Why is this important?

The processes we observed likely lead to unfair judgments of others based on superficial physical features that tell us little about their actual personal attitudes. Especially individuals who look prototypical of their group may be met with more skepticism and negativity in encounters with members from other racial groups but also with members of their own group. By being aware of this bias, we can try to correct for it and thereby reduce its influence when we form first impressions about other people.

Reference to the research article

Kunst, Jonas R.; Dovidio, John F.; Bailey, April & Obaidi, Milan (2022). The Way They Look: Phenotypic Prototypicality Shapes the Perceived Intergroup Attitudes of In- and Out-group Members. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2022.104303