By performing a meta-analysis on 53 studies conducted in 2020 and 2021, we demonstrated under which conditions believing in COVID-19 conspiracy theories influences prevention responses.

By Silvia Allegretta, Kinga Bierwiaczonek, Jonas R. Kunst

What are COVID-19 conspiracy theories?

In the 21st century, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the constant stream of information coming at us from all angles. With so much information at our fingertips, it can be difficult to separate fact from fiction—especially when it comes to news stories that have the potential to provoke strong reactions and divisive opinions in readers.

Conspiracy theories are explanations for events or situations that are not widely accepted by the general population. These theories often involve secret cabals, fictitious plot points, and far-fetched ideas about covert operations being carried out under our very noses. Many of these conspiracy theories center on well-known events or figures from history—and some contain kernels of truth that have been warped and exaggerated beyond reality.

Conspiracy theories offer alternative explanations of events or phenomena, often opposing the official explanations provided by experts, institutions, or governments. They tend to become more prevalent during societal crises. Indeed, the coronavirus outbreak has led to an unprecedented spread of conspiracy theories. Already in January 2020, the idea that COVID-19 could have been spread because of an “accidental leakage” from a bio lab in Wuhan started gaining popularity.

This theory was then endorsed by state officials like former US President Donald Trump and the US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, resulting in international tensions. Other popular conspiracy theories include the belief that the virus was a manufactured bioweapon or that Bill Gates was involved in spreading the disease. Given the massive dissemination of fake news, the World Health Organization (WHO) has defined the COVID-19 pandemic as an “infodemic.” This overabundance of information makes it hard for the reader to identify which news and sources are reliable and truthful.

Four major types of COVID-19 conspiracy theories exist:

- Hoax: Some conspiracy theories contend that the COVID-19 pandemic was entirely made up. It does not exist.

- Big Pharma: People who believe in the Big Pharma conspiracy theory think that pharmaceutical companies either created or made up the virus to profit from it financially.

- Political conspiracy: Some theories argue that the COVID-19 virus and pandemic were created to control people and to increase the political power of some groups.

- Bio Weapon: Some theories contend that COVID-19 is a bioweapon that was intentionally or unintentionally released.

While this lists some major types of COVID-19 conspiracy theories, many more exist. Moreover, conspiracy theories often combine elements from different categories.

The impact of COVID-19 conspiracy theories on health behavior

While some state officials actively contributed to the spread of conspiracy beliefs during the pandemic, health officials warned that conspiracy theories might have disastrous consequences for how people respond during the coronavirus pandemic. For example, COVID-19 conspiracy theories may dissuade people from complying with health guidelines and getting vaccinated or even motivate people to seek alternative treatments. To test if that is true, we conducted the first meta-analysis on this topic and analyzed data from 53 published and unpublished manuscripts from 2020 and 2021. Indeed, our meta-analysis showed that conspiracy theories predict people’s reluctance toward coronavirus prevention measures. Although some of the effects were small, they may still be very dangerous on a global scale.

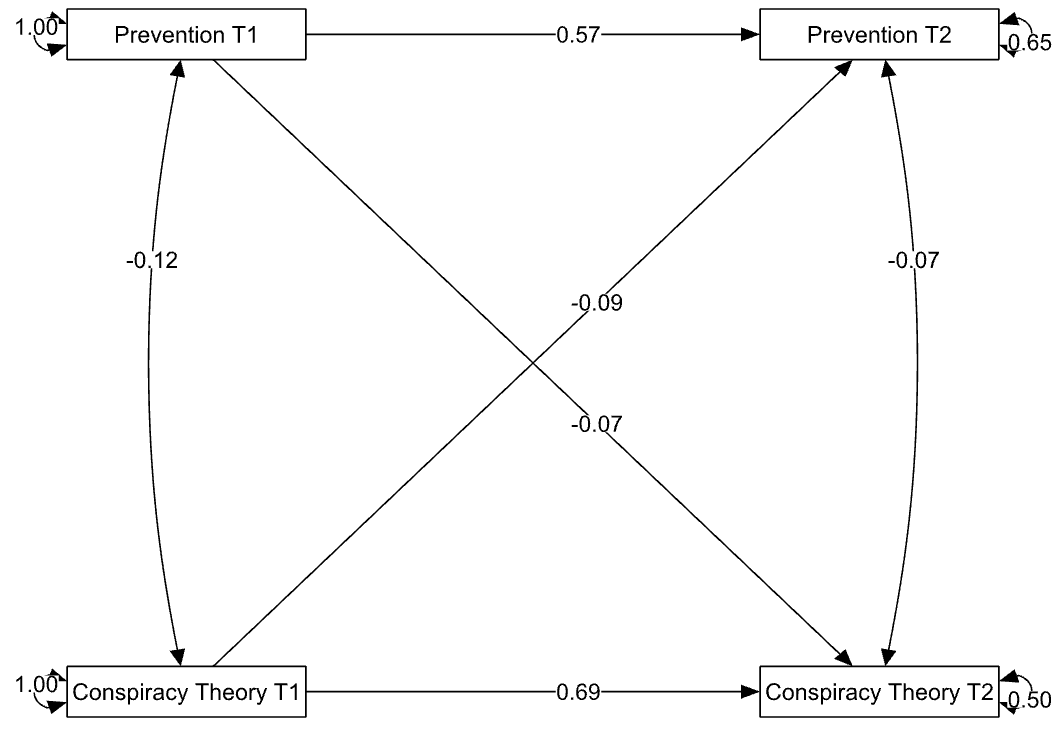

To see how the effects of coronavirus conspiracy theories on health-related responses behave over time, we integrated the results of all available longitudinal studies on this topic. We found that the more people believed in COVID-19 conspiracy theories at one point in the pandemic, the more they tended to be reluctant about prevention measures later.

To see how the effects of coronavirus conspiracy theories on health-related responses behave over time, we integrated the results of all available longitudinal studies on this topic. We found that the more people believed in COVID-19 conspiracy theories at one point in the pandemic, the more they tended to be reluctant about prevention measures later.

Interestingly, we also observed the opposite direction of effects: the more people were reluctant toward prevention measures at one point, the more they were likely to believe in conspiracy theories later on. This finding may mean that people use conspiracy beliefs to justify their behaviors.

Some COVID-19 conspiracy theories are more harmful than others

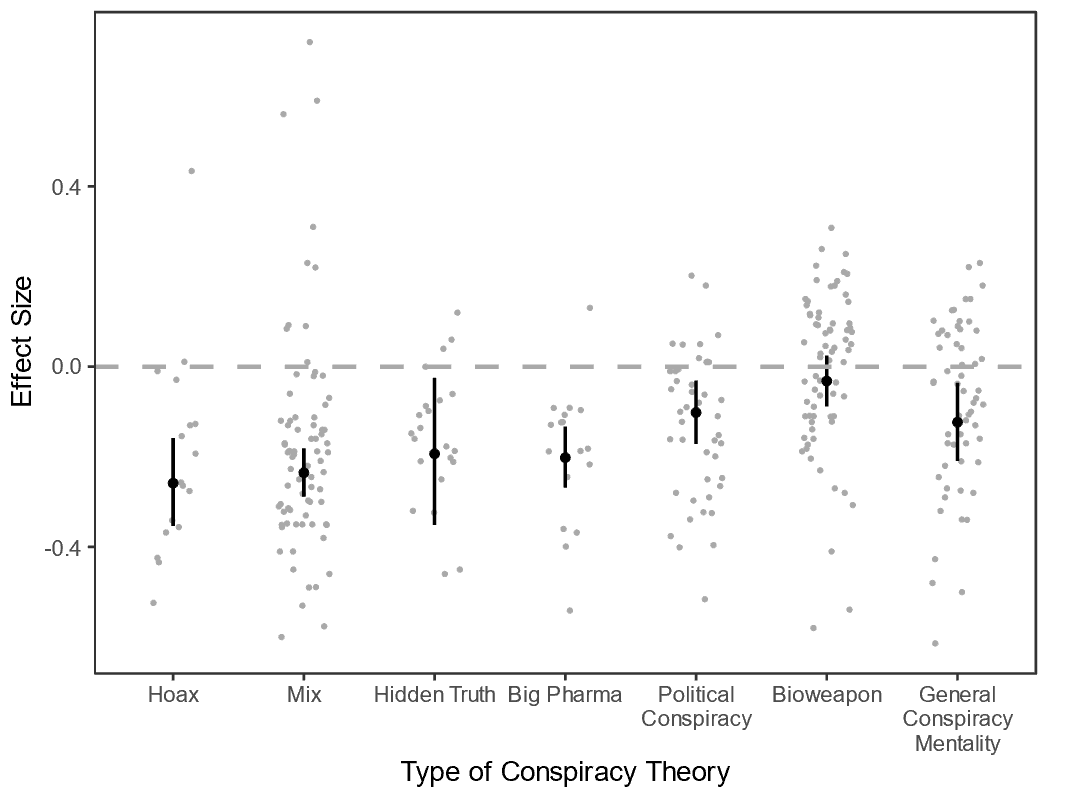

Our next question was whether some COVID-19 conspiracy theories are more dangerous than others. Indeed, this seems to be the case. Of all tested COVID-19 conspiracy theories, those that propose that COVID-19 is a hoax seem to be the most dangerous. According to our results, such COVID-19 conspiracy theories have the most significant power to dissuade people from complying with health guidelines.

Our next question was whether some COVID-19 conspiracy theories are more dangerous than others. Indeed, this seems to be the case. Of all tested COVID-19 conspiracy theories, those that propose that COVID-19 is a hoax seem to be the most dangerous. According to our results, such COVID-19 conspiracy theories have the most significant power to dissuade people from complying with health guidelines.

Interestingly, the bioweapon theory seems the least damaging for how people respond to the pandemic, probably because it implies that COVID-19 is lethal, so it makes sense to comply with prevention measures. This observation, however, does not mean that the bioweapon theory is completely inoffensive. Although it does not seem to affect people’s health responses, it may still damage international relations and lead to prejudice, something we did not test in this study.

COVID-19 conspiracy theories influence some prevention measures more than others

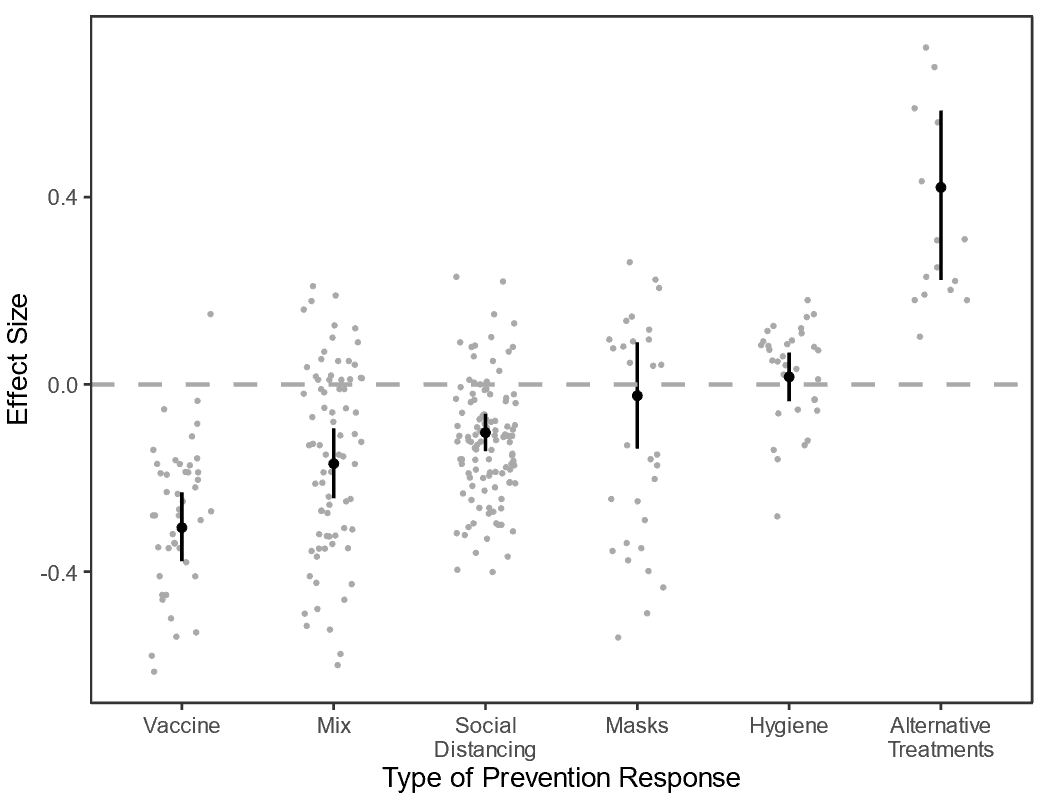

The next question was what kind of health responses are the most susceptible to conspiracy beliefs. We found that people believing in COVID-19 conspiracy theories were reluctant toward vaccination and social distancing but not toward mask-wearing and hygiene (e.g., hand washing). The possible reason is that social distancing and vaccination imply relatively high psychological costs (e.g., loneliness and fear of side effects). Hence, people who do not believe the official narratives about COVID-19 are less willing to “pay” these costs but can still engage in less costly measures such as hand washing.

The next question was what kind of health responses are the most susceptible to conspiracy beliefs. We found that people believing in COVID-19 conspiracy theories were reluctant toward vaccination and social distancing but not toward mask-wearing and hygiene (e.g., hand washing). The possible reason is that social distancing and vaccination imply relatively high psychological costs (e.g., loneliness and fear of side effects). Hence, people who do not believe the official narratives about COVID-19 are less willing to “pay” these costs but can still engage in less costly measures such as hand washing.

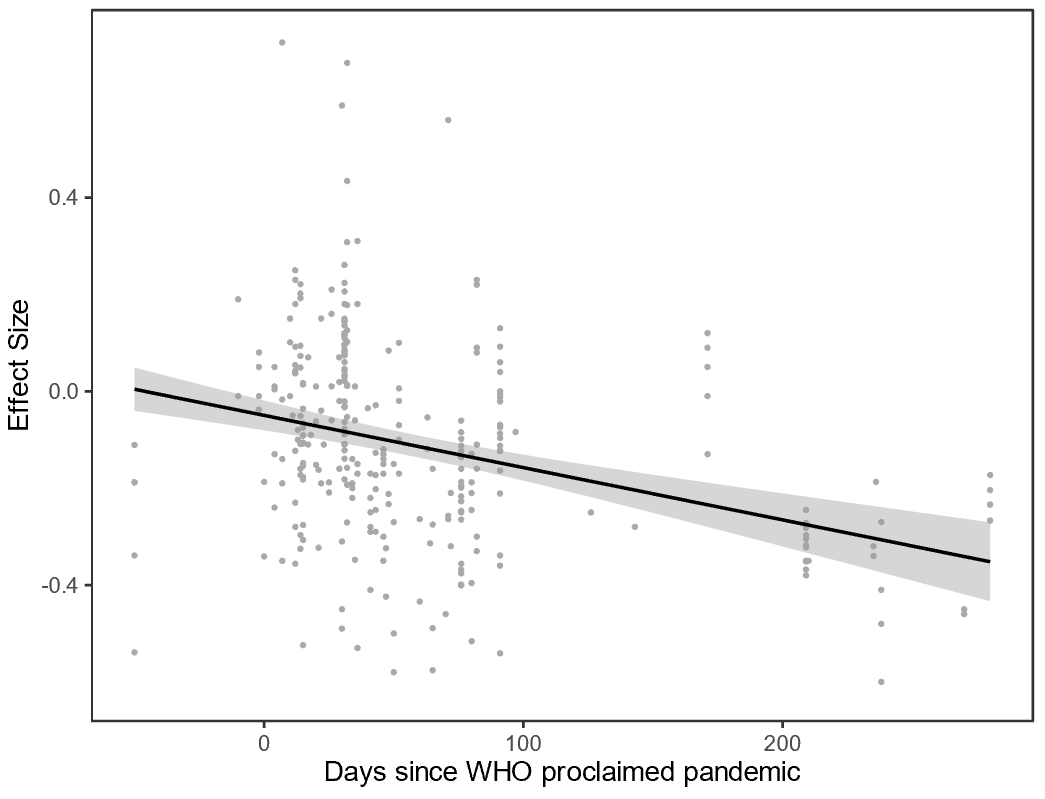

Finally, we tested if the effects of COVID-19 conspiracy theories differed depending on how much time into the pandemic the data were collected. Indeed, the further the pandemic progressed, the stronger the observed negative association between conspiracy beliefs and health responses was. As the pandemic progressed, COVID-19 conspiracy theories became more and more typical for people reluctant toward COVID-19 prevention. Those who were initially hesitant for other reasons (e.g., because they questioned the safety or effectiveness of the measures) may have become less reluctant later. Alternatively, reluctant people started adopting COVID-19 conspiracy theories to justify their own reluctance.

Finally, we tested if the effects of COVID-19 conspiracy theories differed depending on how much time into the pandemic the data were collected. Indeed, the further the pandemic progressed, the stronger the observed negative association between conspiracy beliefs and health responses was. As the pandemic progressed, COVID-19 conspiracy theories became more and more typical for people reluctant toward COVID-19 prevention. Those who were initially hesitant for other reasons (e.g., because they questioned the safety or effectiveness of the measures) may have become less reluctant later. Alternatively, reluctant people started adopting COVID-19 conspiracy theories to justify their own reluctance.

Why is this important?

Given the global impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had in recent years and still has today, raising awareness of the dangers of conspiracy theories is extremely important. Unfortunately, throughout the pandemic, COVID-19 conspiracy theories were deliberately nourished by politicians, media, and even the scientific community. Our results show that such endorsements are more than irresponsible because the consequences of conspiracy theories can be disastrous. Our meta-analysis provided robust evidence that, during the pandemic, COVID-19 conspiracy theories dissuade people from adhering to health guidelines. They might, therefore, seriously undermine global efforts to contain the virus.

References:

Bierwiaczonek, K., Kunst, J. R., & Gundersen, A. B. (2021, September 9). The role of conspiracy beliefs for COVID-19 prevention: A meta-analysis.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101346

Bierwiaczonek, K., Kunst, J. R., & Pich, O. (2020). Belief in Covid‐19 conspiracy theories reduces social distancing over time. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 12(4), 1270–1285.

https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12223