When majority-group members acculturate, they adopt the aspects of minority-group cultures, such as attitudes, behaviors, and cultural norms, to varying degrees. But when does such acculturation become cultural appropriation? How do minority-group members perceive it? A new study from our lab provides some first insights.

By Dena Mohebbinooredinvand

What is majority-group acculturation?

Acculturation refers to cultural and psychological change resulting from intercultural contact. It involves various changes in an immigrant’s psychological, social, cultural, and economic life domains. In theory, acculturation involves mutual accommodation and change by all individuals from all groups involved in intercultural contact. However, most research has focused on cultural change experienced by those self-identifying as minority-group and majority-group members. Thus, we know relatively little about cultural changes among majority-group members.

Majority-group acculturation refers to the process by which members of the dominant cultural group adjust to the presence and influence of minority groups in their society. This complex process involves various dimensions, including changes in attitudes, behaviors, and values towards the minority group and changes in the dominant society’s broader social and cultural norms.

Understanding majority-group acculturation is essential for promoting positive intergroup relations and reducing prejudice and discrimination towards minority groups. These cultural changes in majority groups can also affect the way we understand migrants’ acculturation strategies and preferences, so it is necessary to shed light on majority group acculturation.

Let us take Germany as an example – the Western European country home to the largest Turkish population outside Turkey. Considering the influx of immigrants from different cultures, it seems naive to consider today’s Germany the same as a century ago. If one nowadays walks the streets of various cities in Germany, such as Berlin and Frankfurt, one can easily find restaurants, local ingredients, shops, and communities all over the city from other ethnicities like those originating from Turkey.

Thus, Germans’ life is altered compared to decades ago. Today, a German might eat a simit (Turkish bread) for breakfast, then go to work, talk to Turkish colleagues, and meet friends with a Turkish background in a Turkish restaurant. Indeed, Döner kebab has become a popular street food in Germany, reflecting the lasting influence of Turkish cuisine.

The presence of Turkish people in Germany has facilitated cultural exchange and enrichment. Turkish cultural festivals, music, dance, and art exhibitions have become an integral part of the cultural landscape in many German cities. This exposure has broadened German perspectives, fostering an appreciation for other traditions, celebrations, and artistic expressions. Besides, Turkish is one of the most widely spoken languages among immigrant communities in Germany. Turkish-German bilingualism has led to a blend of language and cultural influences. Turkish phrases and words have been incorporated into colloquial German, especially in regions with a significant Turkish population.

The presence of Turkish people has challenged and shaped societal attitudes and policies toward multiculturalism, diversity, and integration. Turkish Germans have played vital roles in politics, arts, sports, academia, and other fields, contributing to the overall cultural landscape of Germany.

In addition, Turkish fashion designers and artisans have made their mark in Germany, infusing their designs and craftsmanship into the fashion industry. This influence is visible in clothing styles, accessories, and traditional Turkish textiles incorporated into contemporary fashion trends.

Many Turkish Germans also have a passion for sports, particularly football (soccer), which has influenced the sporting culture in Germany. Turkish German players have represented Germany in international competitions, contributing to the success of German national teams. In addition, sports clubs and leagues in Germany have created spaces for community engagement and cross-cultural interactions.

In sum, when we describe the daily life of a majority ethnic German today and compare it to the past, we witness substantial changes. Therefore, if we want to gain a more complete picture of acculturation research, it is insufficient to focus only on minority groups. Instead, we must explore the intriguing gap in acculturation research: Majority-group acculturation.

The relation between majority-group acculturation and cultural appropriation

But when is majority-group acculturation genuine change, and when does the minority perceive it as cultural appropriation? In research, cultural appropriation is often defined as similar to cultural adoption. It is used to describe the adoption or use of aspects of a culture, such as symbols, artifacts, genres, rituals, fashion, music, or technologies, by members of another culture.

What is Cultural Appropriation?

Cultural appropriation is a concept in sociology that refers to the adoption or imitation of elements of one culture by members of another culture. This can involve using traditional clothing, language, art, religious symbols, and social behavior, often without understanding or respecting the original culture and context.

Cultural appropriation is generally viewed as problematic, particularly when members of a dominant culture appropriate elements of a marginalized, less privileged culture for their own use. This can be seen as an exploitative act, as it often involves the appropriation of elements without permission and without any acknowledgment or understanding of their cultural significance. In many cases, the appropriating culture may reap social or economic benefits from these cultural elements, while the originating culture may not.

Cultural appropriation can lead to widespread misunderstanding about the cultures being appropriated and can reinforce stereotypes. It can also result in cultural elements being taken out of context and stripped of their original meanings and significance.

However, the concept of cultural appropriation is also a subject of intense debate. Some argue that cultural exchange is a natural and inevitable part of human interaction and that efforts to police cultural appropriation may inhibit free expression. Others, however, stress the need for greater cultural sensitivity and respect, particularly when dealing with elements of cultures that have been historically oppressed or marginalized.

The Difficulty in Differentiating Cultural Appropriation from Genuine Acculturation

Distinguishing between cultural appropriation and genuine acculturation can be challenging due to the complex nature of cultural exchange. Both processes involve the adoption of elements from another culture, but the contexts, motivations, and impacts of these adoptions vary considerably.

Cultural appropriation often involves a power dynamic, with members of a dominant culture appropriating elements of a marginalized culture, typically without an understanding or respect for their cultural significance. On the other hand, genuine acculturation involves a more reciprocal exchange and is generally marked by a deeper level of engagement and understanding between cultures.

Despite these general distinctions, the line between the two can blur. For instance, someone may genuinely admire and wish to engage with another culture but, due to a lack of understanding, may inadvertently appropriate certain elements in a way that is seen as disrespectful or exploitative.

Asking minority-group members about how they perceive cultural change can be a key tool in discerning between cultural appropriation and acculturation. Minority cultures often have a unique insight into the ways in which their traditions and symbols are being used or misused. Their perspectives can shed light on whether a particular instance of cultural exchange is seen as respectful engagement or damaging appropriation.

However, it is also essential to remember that members of the same cultural group can have different views on cultural appropriation and acculturation. Some may view certain forms of cultural exchange as enriching and positive, while others may perceive the same exchange as exploitative or disrespectful. The interpretations can vary based on individual experiences, values, and beliefs.

Hence, understanding cultural change and distinguishing between cultural appropriation and genuine acculturation requires ongoing dialogue, respect, and a willingness to listen and learn from the perspectives of those whose cultures are being engaged with.

What do minority-group members think of majority-group acculturation themselves?

We tried to find answers to this question by conducting a study investigating acculturation dynamics in a Muslim minority sample living in the U.K. The United Kingdom, especially England, has been a colonial power and can provide interesting insights into majority-minority relations, power dynamics, and potential cultural appropriation.

Finding 1: No clear oppposition to majority-group acculturation

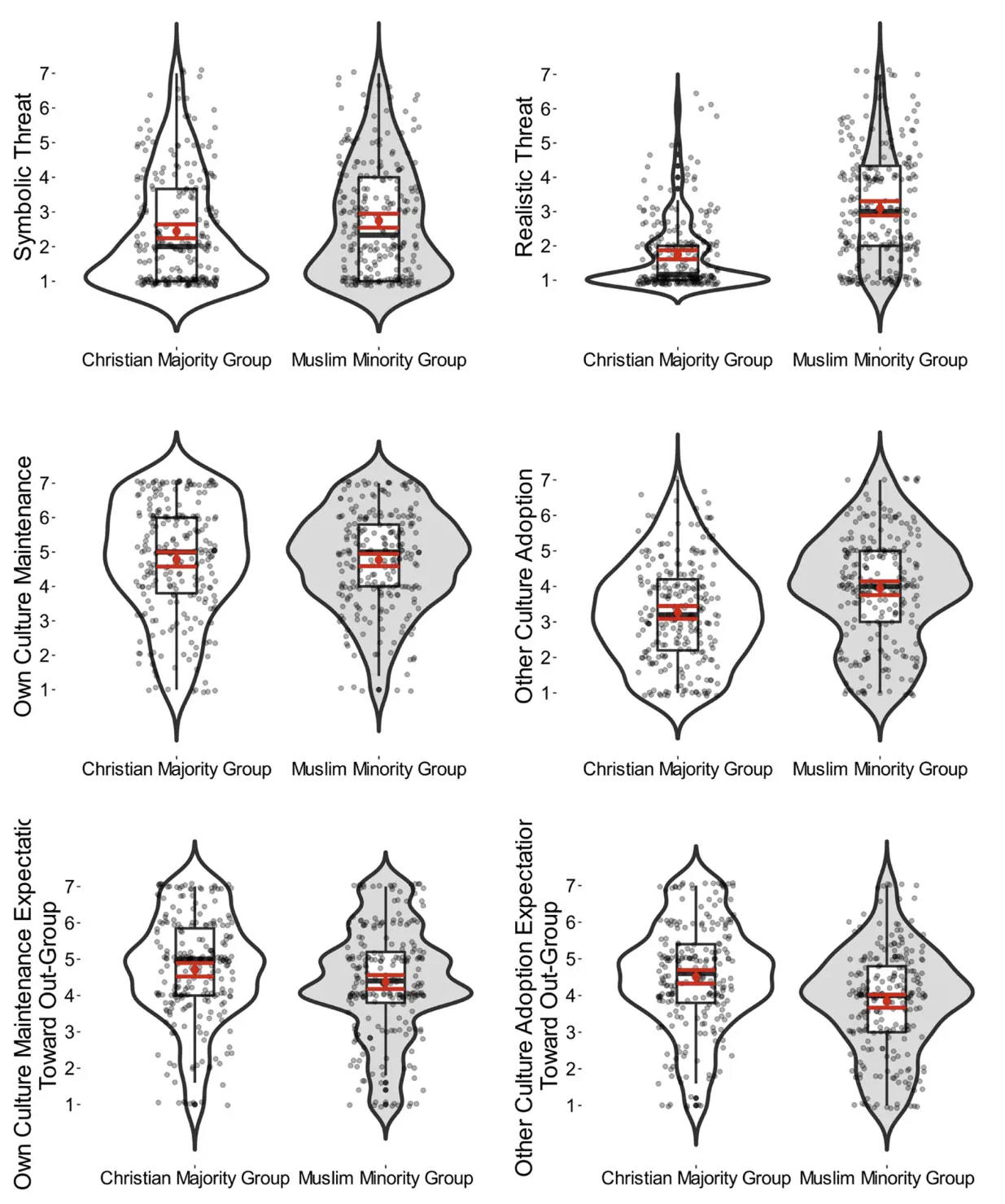

According to our research, Muslim minority-group members have normally distributed acculturation expectations towards White Christian majority-group members. Put differently, at least in this group, minority-group members did not per se reject majority-group acculturation on average, making it unlikely that they saw it as cultural appropriation.

There seems to be no clear opposition to the idea that majority-group members should acquire the culture of minority-group members. On the contrary, many Muslim participants endorsed that majority-group members adopt other cultures. Therefore, at least in this specific context, minority-group members seemed to view acculturation as a mutual cultural change rather than cultural appropriation.

Finding 2: No relationship with threat perceptions

Furthermore, the acculturation expectations that minority-group members held were not rooted in realistic or symbolic threat perceptions. Realistic threats refer to the tangible threats individuals perceive in their environment, such as economic competition or physical harm. Symbolic threats refer to more abstract threats, such as toward one’s cultural identity, traditions, or values. The fact that acculturation expectations were unrelated to these threat perceptions again makes it unlikely that cultural appropriation concerns influenced them.

These findings cast doubt on the assumption that most Muslim minority group members in the U.K. would, in principle, consider the majority group’s adoption of immigrants’ and minority group’s cultures as cultural appropriation. However, it is essential to note that the study focused on the views of Muslim minority-group members in the U.K., and the results may not be generalizable to other minority groups or different cultural contexts.

Additionally, the study only assessed broader cultural expectations in a limited range of domains. Therefore, it is possible that, although minority-group members generally support majority groups adopting minority cultures, they may regard it as cultural appropriation and find it offensive in other domains.

In conclusion, this study offers valuable insights into the dynamics of acculturation and cultural appropriation within a Muslim minority group residing in the U.K. It appears that these individuals do not generally perceive the majority group’s adoption of their culture as cultural appropriation. Instead, acculturation is seen as a two-way process and is often endorsed by the minority-group members, disputing the notion that they inherently view cultural assimilation by the majority as an act of appropriation.

However, it is important to underline that this study focused solely on a Muslim minority group in the U.K. context. Consequently, the results may not be transferrable to other minority groups or varying cultural contexts. Additionally, given the study’s limited assessment range, perceptions of cultural appropriation might still emerge in other cultural domains, despite the generally positive outlook towards majority groups adopting minority cultures. Further research is therefore recommended to explore these potential nuances and broaden our understanding of cultural dynamics in diverse societies.

Implications and future research

Our findings are significant not only theoretically but also in practice. They have implications for public policies and ways of fostering positive intergroup relations. By understanding the acculturation of the majority, we can help policymakers develop more inclusive and effective strategies for managing cultural diversity. By considering the expectations and perspectives of both minority and majority-group members, conflicts and tensions arising from intercultural interactions can be reduced. We hope to promote greater social cohesion and coexistence by fostering cultural exchange and mutual acculturation.

Reference to the study

Kunst, J. R., Ozer, S., Lefringhausen, K., Bierwiaczonek, K., Obaidi, M., & Sam, D. L. (2023). How ‘should’ the majority group acculturate? Acculturation expectations and their correlates among minority-and majority-group members. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 93, 101779.

Kunst, J. R., Lefringhausen, K., Sam, D. L., Berry, J. W., & Dovidio, J. F. (2021). The missing side of acculturation: How majority-group members relate to immigrant and minority-group cultures. Current directions in psychological science, 30(6), 485-494.