Intractable conflicts are prolonged, stubborn, and often violent disputes that seem immune to resolution. These conflicts, whether they are territorial, or ideological, persist over generations, leaving devastation and division in their wake. In such contexts, hope is often seen as a positive force, that can drive people towards peace and unity. However, research from our lab reveals that collective hope is a multifaceted construct with a paradoxical role: it can both promote peaceful resolution, and facilitate political radicalization.

By Sora Park (intern)

Group-based hope in intractable conflicts

Group-based hope is an emotion, experienced by individuals due to their affiliation with a specific group or society. It is characterized as a forward-looking sentiment that drives individuals toward future goals. This sentiment becomes particularly significant in the sphere of intractable conflicts, where the collective hope may serve as a driving force behind important decisions in international policy.

Often, political organizations make efforts to instill hope among the public, in order to generate support for conflict-related decisions. Therefore, it is important to understand the implications of hope, and consider its potential undesirable consequences. In the literature, hope has been associated with positive intergroup outcomes such as attitudes that favor peaceful resolution. However, we argue that the relationship between hope and conflict-related attitudes are more nuanced, and that a distinction can be made between hope for peace and hope for victory.

Hope directed toward achieving peace involves a desire for resolution, harmony and the cessation of conflict, emphasizing dialogue, understanding, and compromise. Conversely, when people hold hope for victory, they may dehumanize the other group, have less empathy, and justify unethical actions, including the use of personal violence or extreme militant actions.

Hope for victory and support for violence

In a series of studies, we showed that hope for victory and hope for peace are differentially related to conflict-related attitudes. In a survey study conducted among Israeli Jewish students, we analyzed how hope for peace and hope for victory are linked to conflict-related policy support, namely support for compromise, support for extreme war policies, and violent behavioral intentions.

We found that hope for peace was related positively to support for compromise, and negatively related to extreme war policies. For violent intentions, no statistically significant relation was found. Hope for victory, conversely, was related negatively to support for compromise, and positively to both endorsement of extreme militant actions and violent intentions against the outgroup. Additionally, we found that hope for peace was positively, but weakly related to hope for victory. This tells us that the two constructs of hope should not be seen as two mutually exclusive concepts, but rather as two domains of the same emotion that have differing outcomes in behavioral intentions and attitudes.

Evidence from a different context: the Indo-Pakistani conflict

To replicate these findings, we conducted the same study in a different context, namely that of the conflict between Pakistan and India, in the region of Kashmir. This conflict shares similarities with the Israeli-Palestinian dispute before the recent outbreak of war, characterized by recurring violence and the constant threat of war, amidst various attempts to achieve peaceful resolution. We evaluated the same factors as in the first study, this time among Muslim Pakistani students, adjusting the measures to fit the context of the Indo-Pakistani conflict.

We found results consistent with those in the Israeli-Palestinian context. In that, hope for victory over India was linked to higher support for radical war policies and violent intentions, along with reduced support for compromise. Furthermore, consistent with of Study 1, we found a weak but positive relationship between hope for peace and hope for victory.

Uncovering hope-profiles: victory hopers, peace hopers and dual hopers

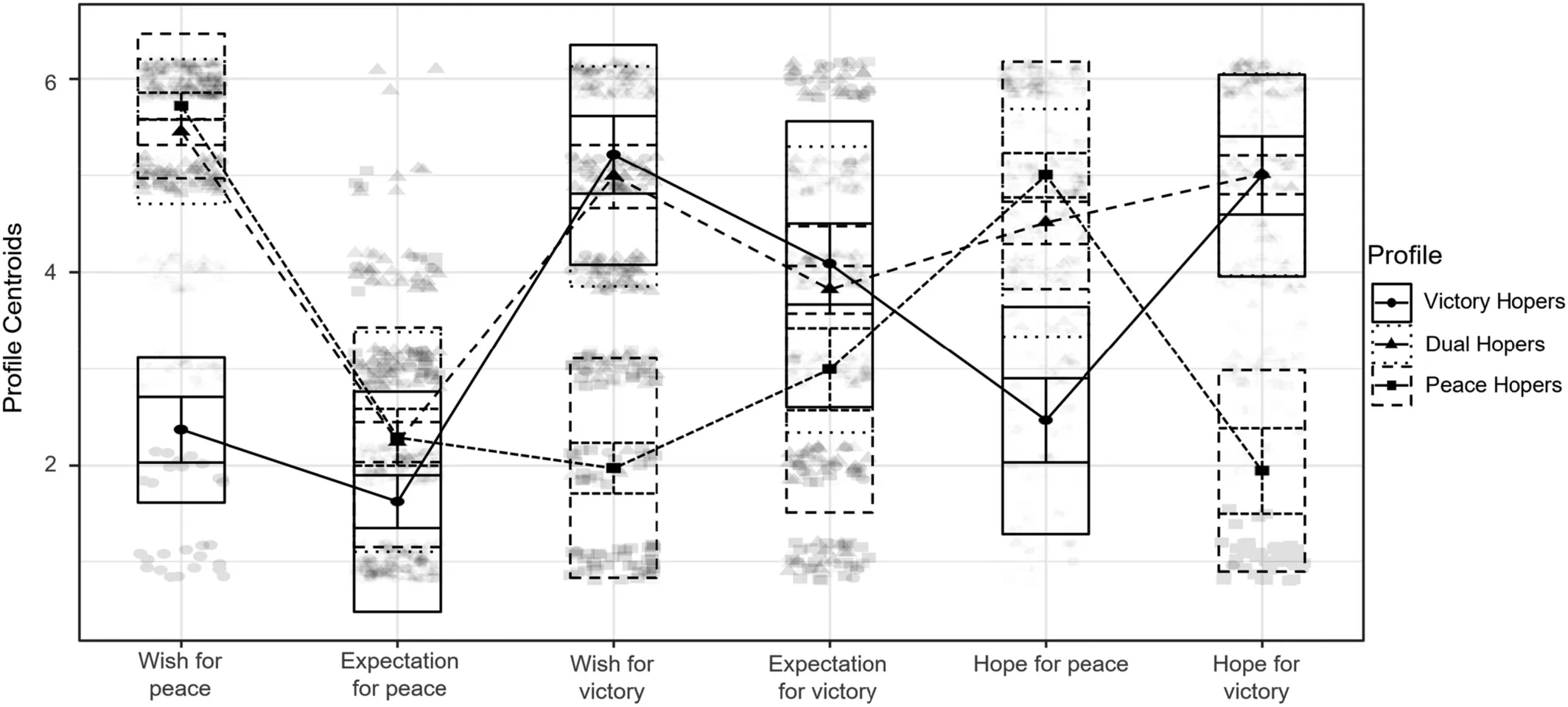

In our two initial studies, we discovered a weak but positive correlation between the two types of hope. Intuitively, hope for peace and hope for victory may seem to pull in opposite directions, but our findings indicate that the two constructs can be correlated and can co-exist within individuals, and suggest an underlying common motivational and emotional-cognitive factor. In a following study, we aimed to assess both types of hope and their cognitive evaluations. This time, we not only measured wishes and expectations, but incorporated desirability and expectancy as components, as suggested by appraisal theories.

We used latent profile analysis, a data-driven technique that classifies cases into latent subgroups that are not directly observable. In a survey among Israeli Jewish adults we measured their wish and expectation for peace/victory, hope for peace/victory, peace-over-victory preference, support for compromise, support for extreme war policies, and support for violence.

Our studies revealed three distinct hope profiles among participants:

- Victory Hopers (18.1%): High hope for victory, low hope for peace. More likely to be non-secular males without education, politically right-leaning, and younger. More focused on achieving a decisive victory and having a confrontational orientation.

- Dual Hopers (54.3%): High hope for both peace and victory. Predominantly right-wing secular Jews with varied religiousness levels, showing a nuanced orientation striving for conflict resolution that may be based either on peace or victory.

- Peace Hopers (27.6%): High hope for peace, low hope for victory. Wished for a peaceful resolution, prioritized peace over victory. More likely to be academically educated, secular women with mixed political orientations.

The results aligned with the first two studies, providing even more support for the differential role of hope. Dual hopers represented the largest subgroup, showing again that individuals can hold both peace and victory hopes simultaneously. This may seem conflicting, but it may just be a reflection of the complex nature of humans within conflict, where individuals desire a peaceful resolution, while also feeling a need to stand up for their country’s rights and achieve victory. Although dual hopers show a higher peace-over-victory preference than peace hopers, they may be still be at risk of radicalization as they show high support of extreme war policies and violent intentions.

Another notable finding is that even among those hoping for peace, expectations for peace were generally low. The fact that hope remained present across all profiles suggests that one can hold hope, even without having confidence in achieving it. The manifestation of hope is thus not dependent on realistic beliefs, but it is rooted in perseverance even when the odds are unfavorable.

How does hope change over the course of a war?

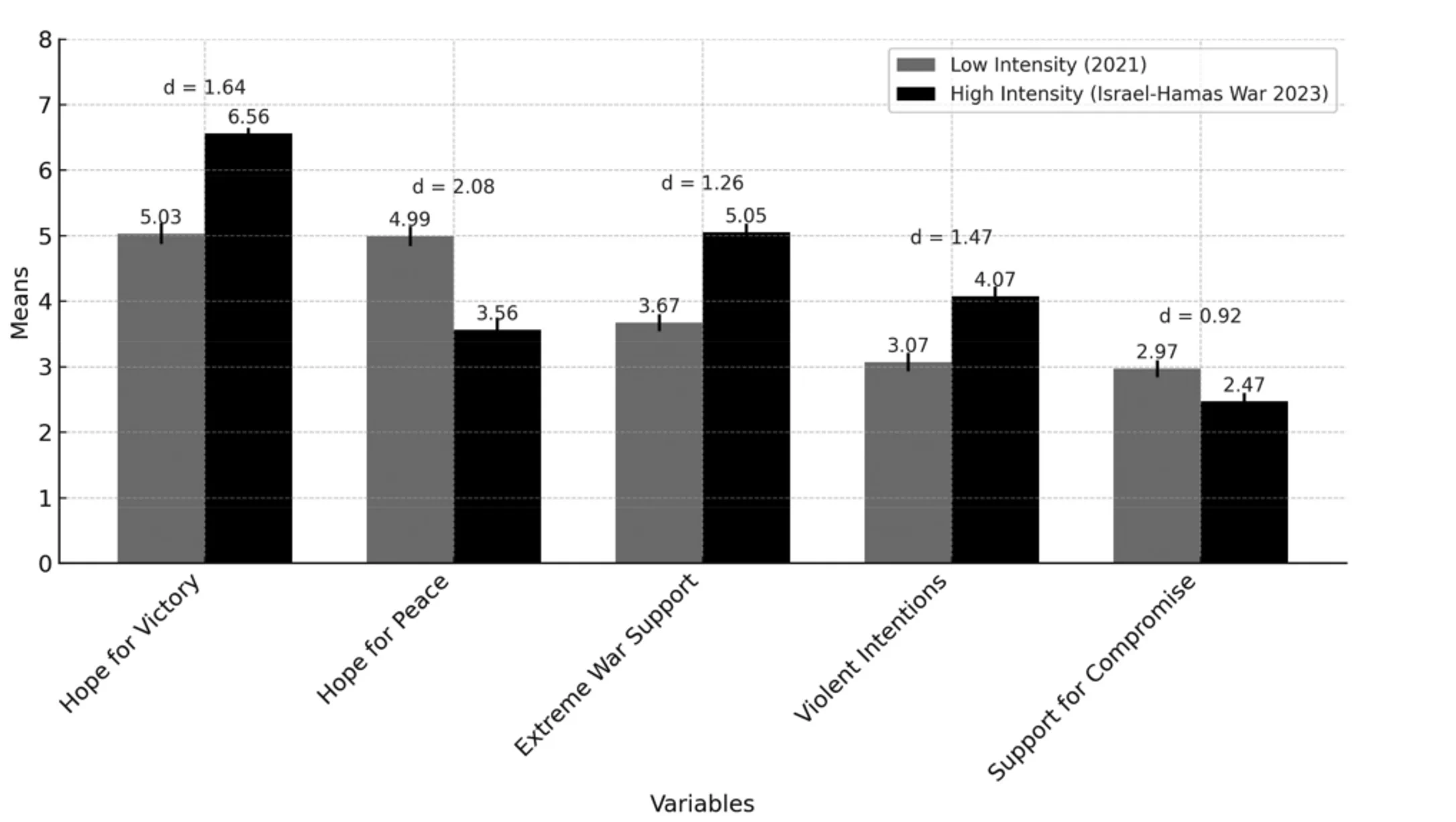

In a subsequent study, we aimed to explore the factors driving war mobilization within the Israeli society, as well as the stance of Israeli political and military leaders advocating for the nation’s victory over Hamas. In a longitudinal assessment, we inspected how hope differed between points of low and high conflict intensity. We analyzed survey data among a sample of Israeli Jews before (2021) and during the 2023 Israel-Hamas war.

In doing so, we found a substantial increase in hope for victory, support for extreme war practices, and violent intentions, while hope for peace and support for compromise decreased. This shift coincided with increased intentions for personal violence and support for extreme militant measures, including actions potentially bordering war crimes, such as the disregard for the lives of civilians. Another notable finding was that during the period of low conflict intensity, levels of hope for peace and hope for victory were relatively balanced. In contrast, when conflict-intensity was increased, the difference between the two types of hope grew larger.

Figure 1

Differences in hope for victory between low and high conflict intensity in Study 4.

Furthermore, we found a direct correlation between increased hope for victory and an increase in support for extreme war tactics and violent intentions. These findings not only align with our previous results, but also provide temporal evidence for the role of hope for victory on radicalized conflict behavior, opposing that of hope for peace. Surprisingly, although hope for peace largely decreased, support for compromise was less strongly affected, which suggests that individuals may still support to peace-favoring policies even when conflict is heightened.

Countering radicalization: Instilling hope for peace, not victory

Taken together, the four studies contribute to a nuanced understanding regarding the role of hope for peace and hope for victory in persistent intergroup conflicts. While hope for peace is related to peace-promoting attitudes, hope for peace may foster support for more extreme militant actions which may in turn fuel further conflict.

Based on these findings, we propose that interventions aimed at countering extremism and fostering reconciliation should focus on instilling hope for peace, while reducing hope for victory. This may be achieved by emphasizing the costs of war and the limits of power, promoting cooperation and peace, and simultaneously negating the feasibility and benefits of victory. However, it should be noted that hope for peace and victory sometimes go hand in hand as shown in our studies. This means interventions must to be designed carefully to ensure that increases in hope for peace do not imply more peace for victory.

Reference to research:

, , , , , , , & (2024). Between victory and peace: Unravelling the paradox of hope in intractable conflicts. British Journal of Social Psychology, 00, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12722

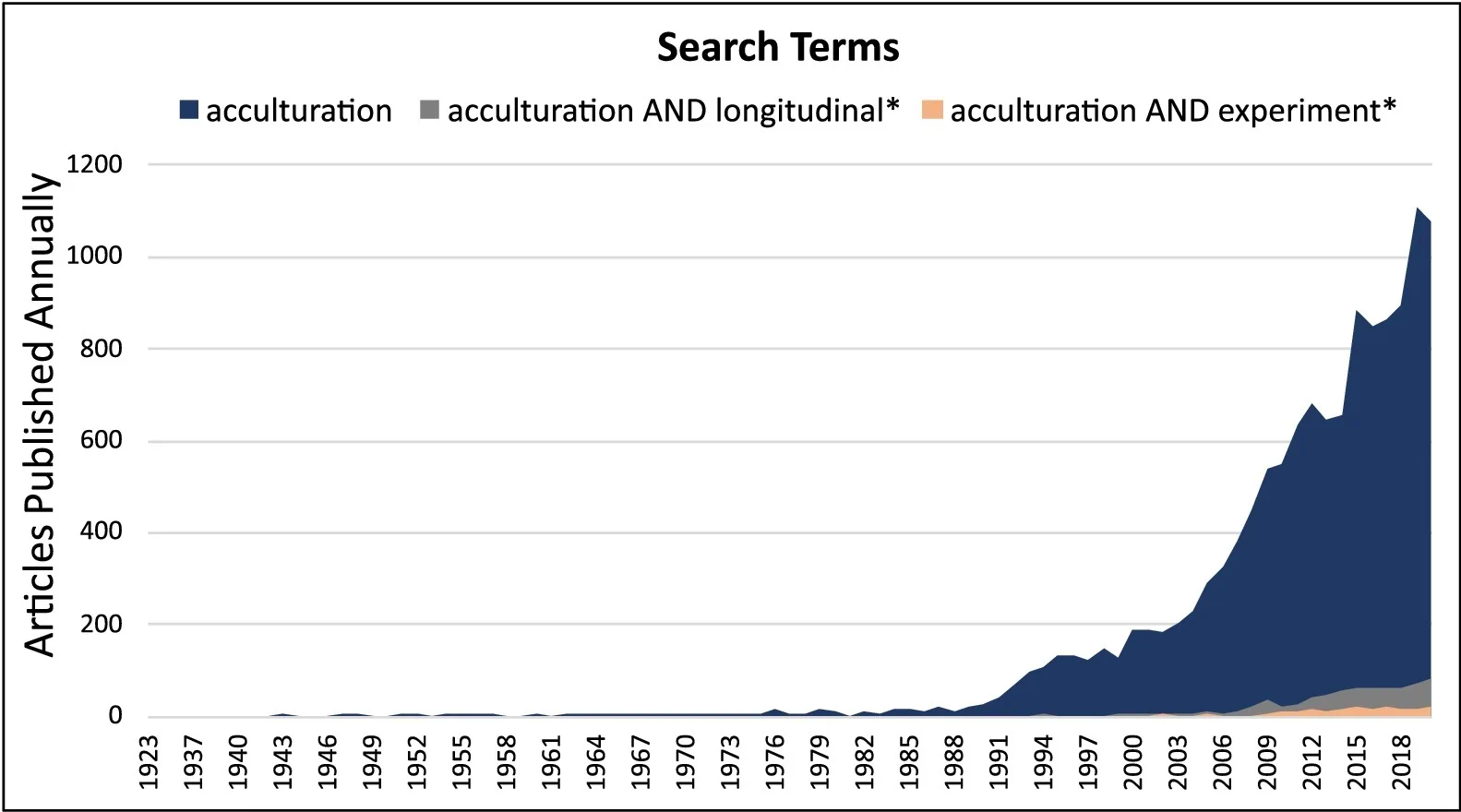

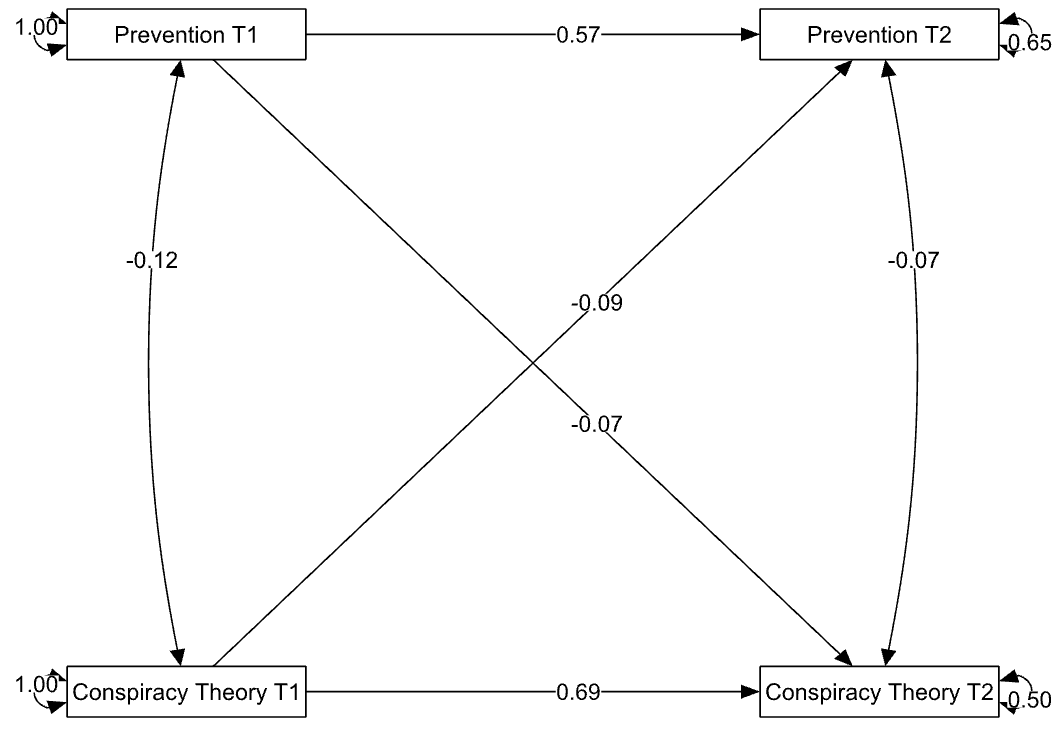

To see how the effects of coronavirus conspiracy theories on health-related responses behave over time, we integrated the results of all available longitudinal studies on this topic. We found that the more people believed in COVID-19 conspiracy theories at one point in the pandemic, the more they tended to be reluctant about prevention measures later.

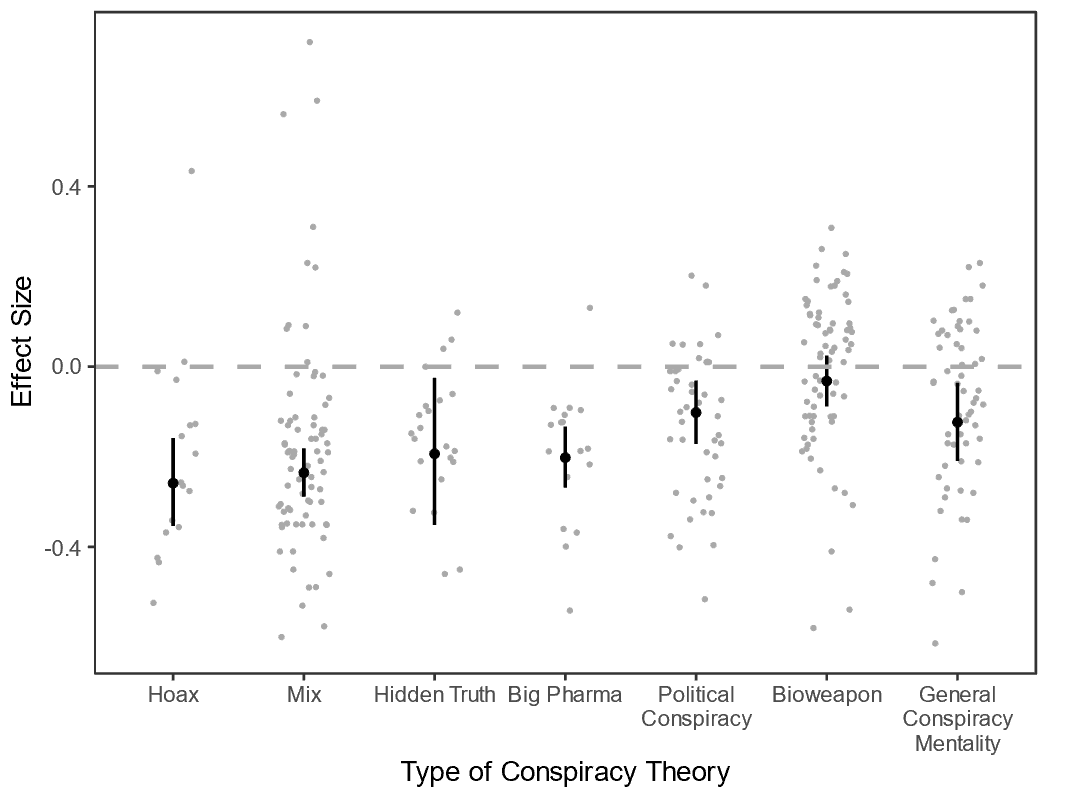

To see how the effects of coronavirus conspiracy theories on health-related responses behave over time, we integrated the results of all available longitudinal studies on this topic. We found that the more people believed in COVID-19 conspiracy theories at one point in the pandemic, the more they tended to be reluctant about prevention measures later. Our next question was whether some COVID-19 conspiracy theories are more dangerous than others. Indeed, this seems to be the case. Of all tested COVID-19 conspiracy theories, those that propose that COVID-19 is a hoax seem to be the most dangerous. According to our results, such COVID-19 conspiracy theories have the most significant power to dissuade people from complying with health guidelines.

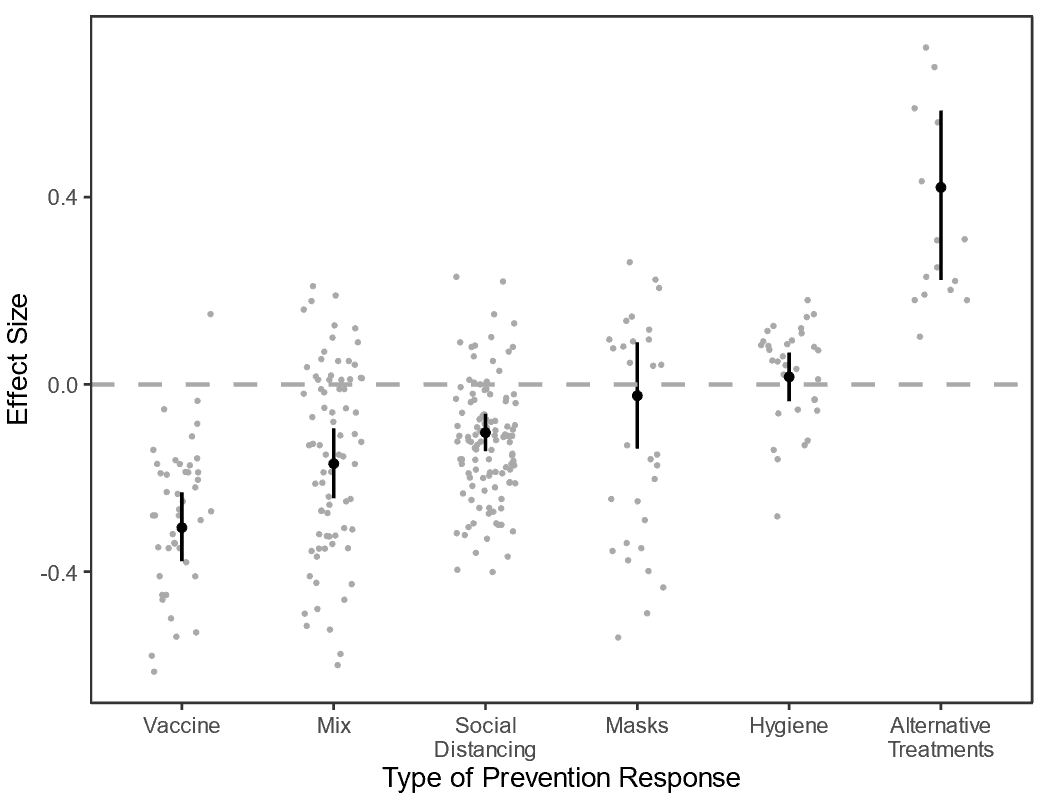

Our next question was whether some COVID-19 conspiracy theories are more dangerous than others. Indeed, this seems to be the case. Of all tested COVID-19 conspiracy theories, those that propose that COVID-19 is a hoax seem to be the most dangerous. According to our results, such COVID-19 conspiracy theories have the most significant power to dissuade people from complying with health guidelines.  The next question was what kind of health responses are the most susceptible to conspiracy beliefs. We found that people believing in COVID-19 conspiracy theories were reluctant toward vaccination and social distancing but not toward mask-wearing and hygiene (e.g., hand washing). The possible reason is that social distancing and vaccination imply relatively high psychological costs (e.g., loneliness and fear of side effects). Hence, people who do not believe the official narratives about COVID-19 are less willing to “pay” these costs but can still engage in less costly measures such as hand washing.

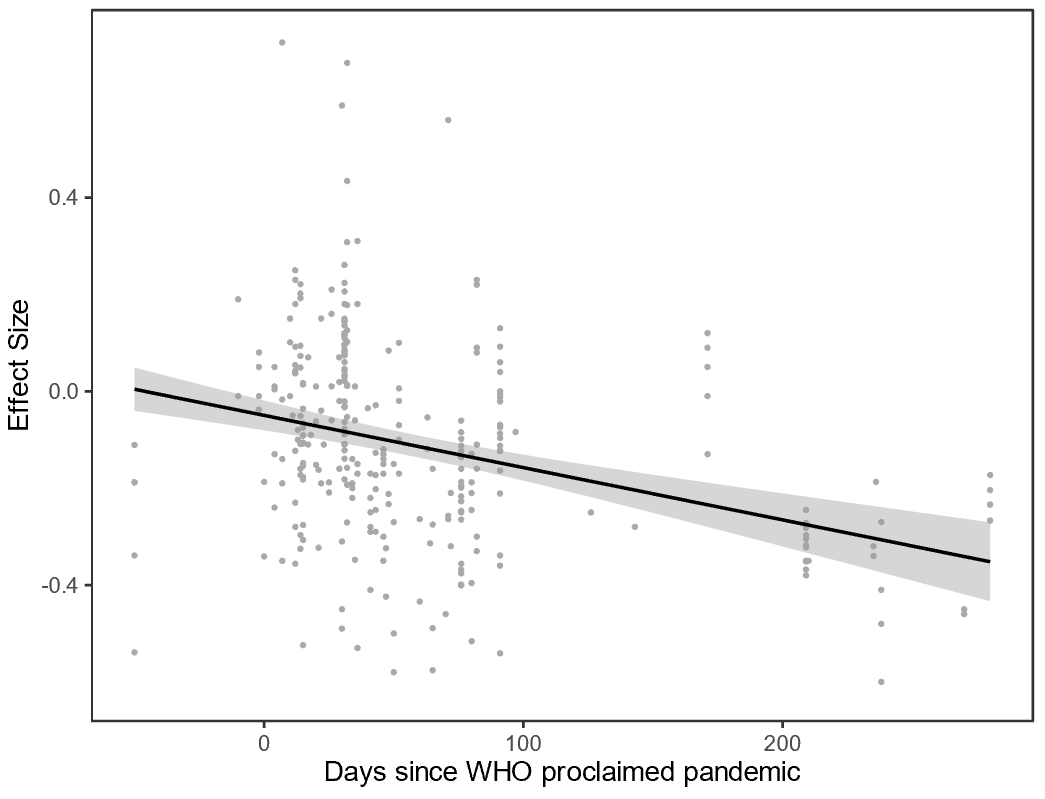

The next question was what kind of health responses are the most susceptible to conspiracy beliefs. We found that people believing in COVID-19 conspiracy theories were reluctant toward vaccination and social distancing but not toward mask-wearing and hygiene (e.g., hand washing). The possible reason is that social distancing and vaccination imply relatively high psychological costs (e.g., loneliness and fear of side effects). Hence, people who do not believe the official narratives about COVID-19 are less willing to “pay” these costs but can still engage in less costly measures such as hand washing. Finally, we tested if the effects of COVID-19 conspiracy theories differed depending on how much time into the pandemic the data were collected. Indeed, the further the pandemic progressed, the stronger the observed negative association between conspiracy beliefs and health responses was. As the pandemic progressed, COVID-19 conspiracy theories became more and more typical for people reluctant toward COVID-19 prevention. Those who were initially hesitant for other reasons (e.g., because they questioned the safety or effectiveness of the measures) may have become less reluctant later. Alternatively, reluctant people started adopting COVID-19 conspiracy theories to justify their own reluctance.

Finally, we tested if the effects of COVID-19 conspiracy theories differed depending on how much time into the pandemic the data were collected. Indeed, the further the pandemic progressed, the stronger the observed negative association between conspiracy beliefs and health responses was. As the pandemic progressed, COVID-19 conspiracy theories became more and more typical for people reluctant toward COVID-19 prevention. Those who were initially hesitant for other reasons (e.g., because they questioned the safety or effectiveness of the measures) may have become less reluctant later. Alternatively, reluctant people started adopting COVID-19 conspiracy theories to justify their own reluctance.