What is majority acculturation?

Majority acculturation refers to the cultural and psychological changes experienced by current or former majority-group members as a result of contact with immigrants or ethnic minority-group members living in the same society. It involves the genuine incorporation of aspects of minority-group culture into majority-group members’ default cultural repertoire and ultimately leads to changes in the mainstream culture at the societal level. Unlike typical conceptions of minority acculturation, majority acculturation focuses on the simultaneous influence of multiple heritages present in highly diverse contexts of acculturation. This process can occur at both an individual and societal level, affecting personal practices, values, identity, language, and norms.

Importantly, when focusing on majority acculturation, we are considering the acculturation orientations and strategies of majority groups, not their acculturation expectations toward immigrants. However, investigating majority-group members’ own acculturation and how it relates to acculturation expectations toward immigrants is an important area of research.

How majority-group acculturation differs from minority-group acculturation

The study of majority acculturation is still in its infancy. Thus, we are still discovering its unique factors and processes. However, two critical elements seem to distinguish majority-group acculturation from minority-group acculturation. First, majority-group acculturation necessitates changes to the traditional culture of a society and its status quo. Second, the majority group typically has more power (social, political, and economic) than immigrants or individuals identifying as minority-group members. People tend to adhere to the status quo rather than pursue change, which is often uncertain. Change stimulated by the increasing presence and potential influence of immigrants or minority-group members is commonly perceived as a threat to the higher status of the majority group, leading to the reinforcement of traditional values.

How do majority-group members acculturate?

Evidence suggests that majority-group members typically tend to adopt only two of the four acculturation strategies commonly observed among immigrants or minority-group members: integration and separation. Integration involves maintaining majority-group culture while also adopting aspects of immigrant and minority-group cultures. Separation, on the other hand, involves maintaining majority-group culture while rejecting immigrant and minority-group cultures. Assimilation and marginalization seem to be rarely used by majority-group members.

Furthermore, a significant number of majority-group members display a “diffuse strategy,” showing no clear-cut preference for any of the four previously identified strategies. This pattern is one of the most common in majority acculturation. An overview by Kunst et al. (2021) of the strategies found in majority acculturation studies can be seen below.

In which domains does majority acculturation take place?

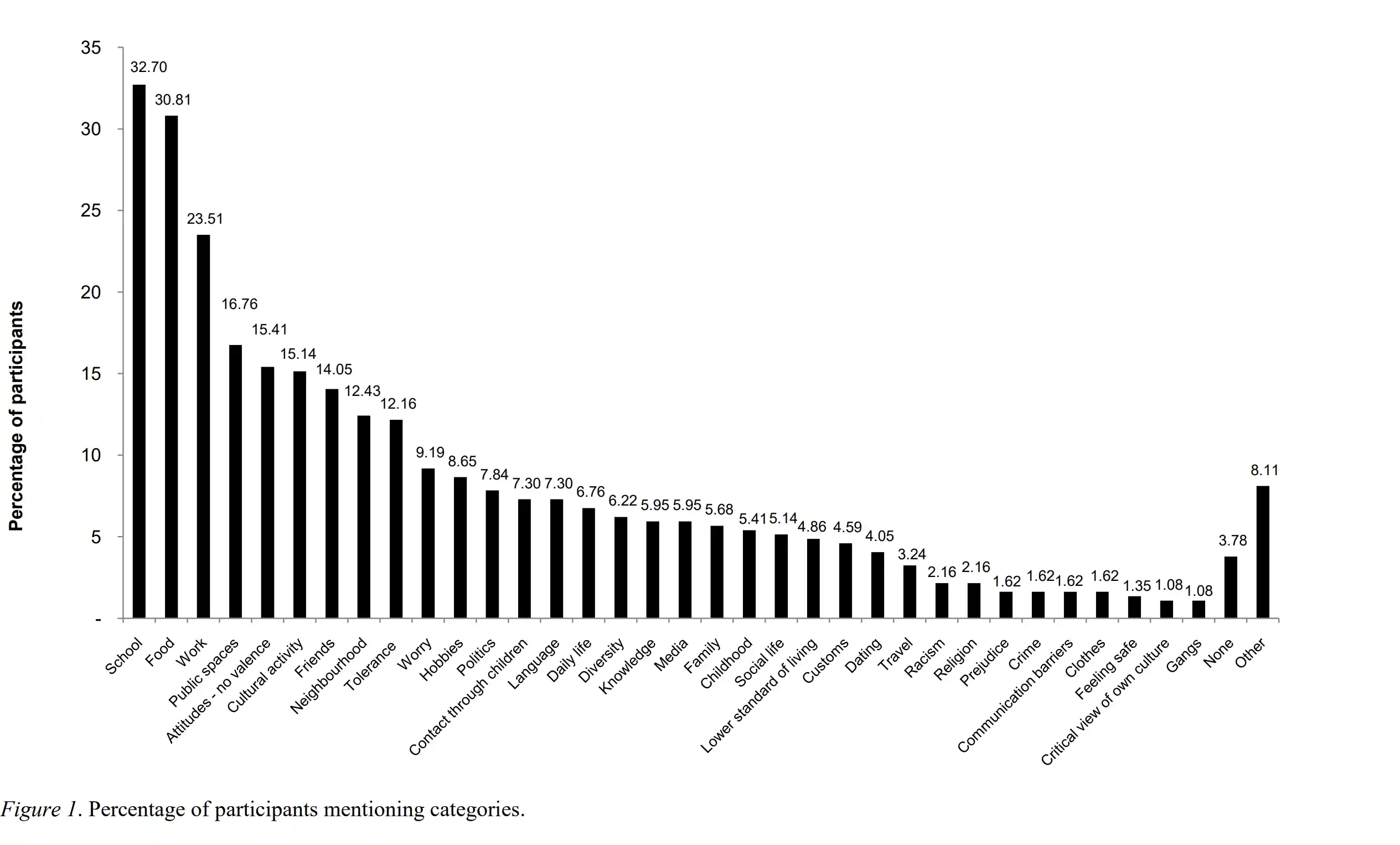

In a mixed methods majority acculturation study by Haugen & Kunst (2017), participants reported cultural influence in a variety of domains such as “School,” “Food,” and “Work,” with food being one major domain due to globalization and the increasing presence of immigrant entrepreneurs in the restaurant and grocery industries.

Work and school are domains where majority-group members are likely to encounter immigrants and gain exposure to different cultures. However, these public arenas are also where immigrants are often expected to adopt majority culture, making it difficult to determine the extent of majority members’ cultural adoption.

The study also found support for domain specificity, with participants reporting more cultural change in terms of behaviors than values. This aligns with research on minority members, suggesting that behavioral change is more vital for functioning in culturally plural surroundings. Majority-group members reported more influence in the private domain, contrasting with minority members who experience cultural change primarily in the public domain.

Conditions of majority acculturation

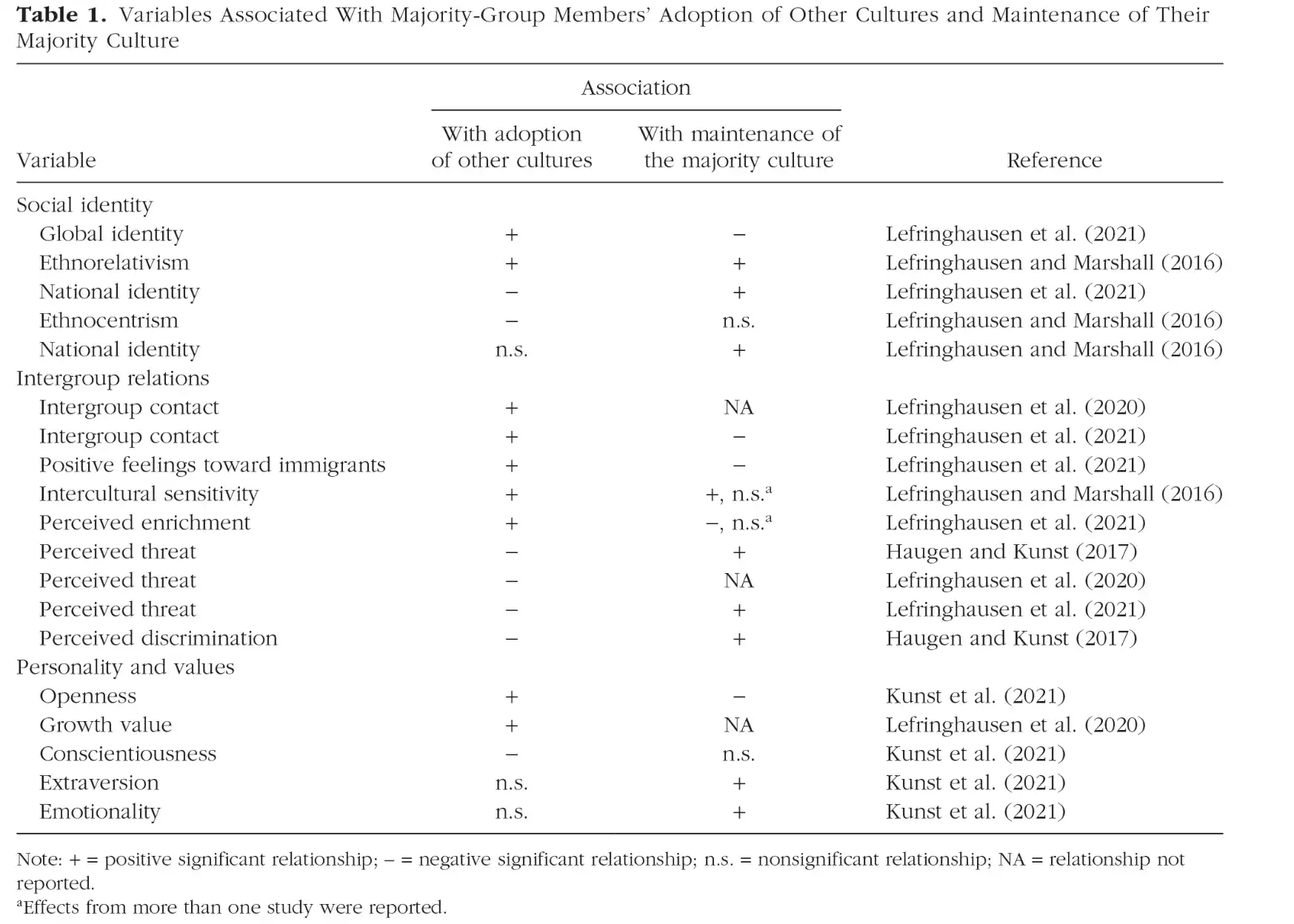

Several conditions may influence majority acculturation, including majority-group members’ willingness to change their group’s culture. At the individual level, factors such as open-mindedness, stronger growth values, less conscientiousness, more frequent intercultural contact, higher-quality contact, cultural sensitivity, and perceiving immigration more as an enrichment than as a threat are associated with greater cultural adoption.

At the group and cultural level, factors such as stronger global identity, being more ethnorelativist, and being less ethnocentric and nationalistic are linked to greater cultural adoption. Conversely, factors such as less openness, less intergroup contact, perceiving immigrants more as a threat, less global identity, and stronger national identification are related to more majority-culture maintenance. For an overview of factors influencing majority acculturation, see the below summary from Kunst et al. (2021):

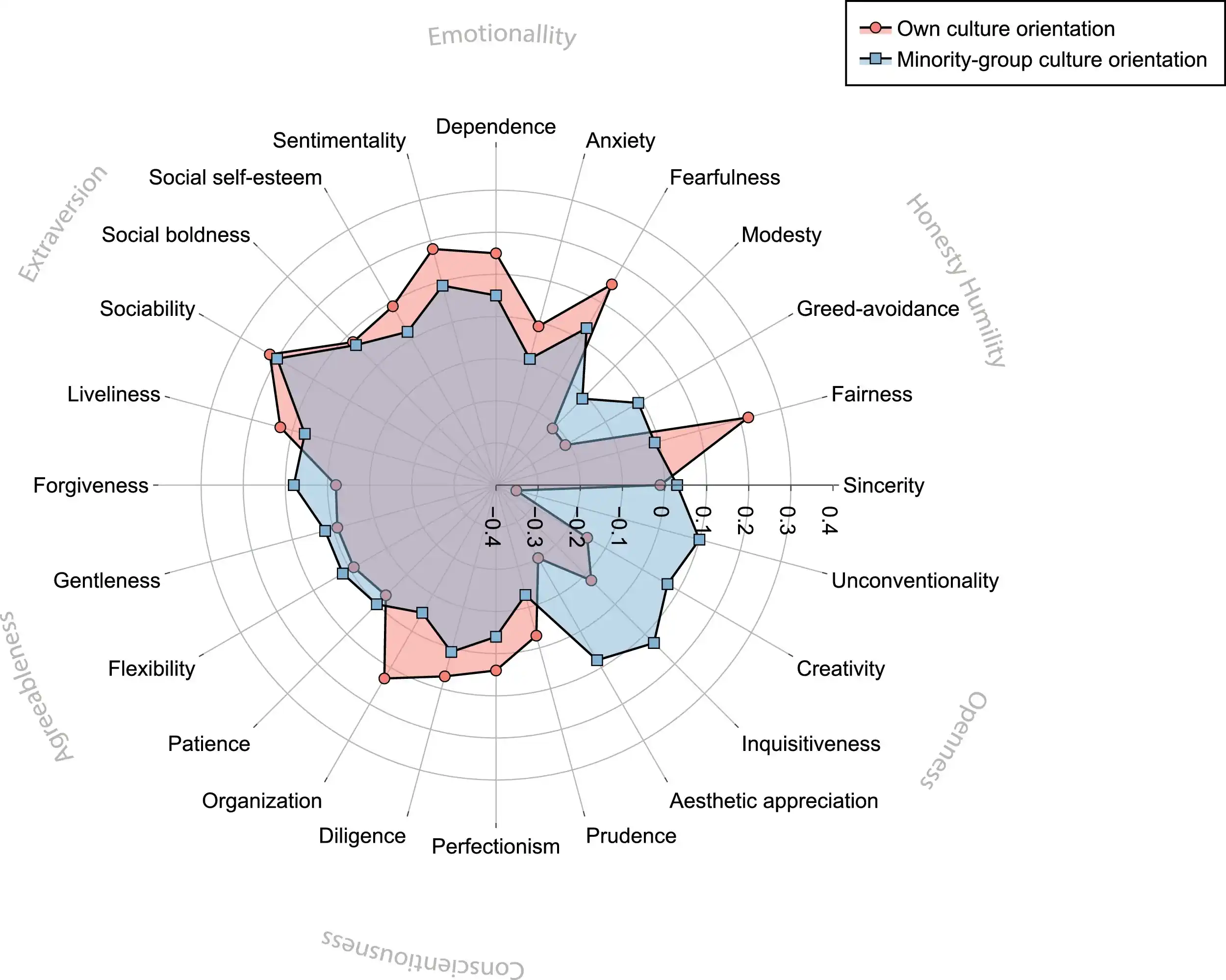

Personality traits and majority acculturation

A study by Kunst et al. (2021) investigated the relationship between the HEXACO personality inventory and majority acculturation. Openness to experience appears to be a significant predictor of adopting minority-group cultures among majority-group members. This finding aligns with research on minority-group members. Interestingly, conscientiousness was found to be negatively related to majority-group members’ adoption of minority cultures. This finding contrasts with previous minority-group work that found conscientiousness to be positively related to minority-group members’ mainstream culture adoption. This discrepancy may be explained by assimilative norms in the U.S. (the context of the study) that encourage minority-group members to adopt the mainstream culture while discouraging majority-group members from adopting minority cultures.

Extraversion and emotionality were found to predict more maintenance of majority-group members’ own culture, while openness to experience predicted less maintenance. This suggests that majority-group members in the U.S. maintain their heritage culture partly to reduce anxiety and ensure a sense of belonging. The relationship between extraversion and the adoption of minority-group cultures, however, remains unclear and may be influenced by factors such as prejudice.

The study identified four acculturation strategies: separation, marginalization, integration, and diffuse. The diffuse cluster displayed a distinct personality profile, characterized by higher openness and lower conscientiousness. This pattern may reflect a blended or hybrid identity that combines aspects of both cultural spheres into something new.

Marginalization emerged as another interesting cluster, with individuals who were less conventional, sentimental, and sociable than those in other clusters. This finding could be interpreted as a reflection of the colorblind approach to diversity prevalent among many U.S. majority-group members.

What are the consequences of majority acculturation?

What are the consequences of majority acculturation?

A new longitudinal study by Lefringhausen et al. (2022) offers a deeper understanding of the societal consequences of majority acculturation. Majority members who maintain their national culture tend to endorse unwelcoming acculturation expectations and ideologies, such as assimilation and exclusionism, which aim to preserve the status quo of the majority culture. On the other hand, those who adopt immigrant culture may be more inclined to support welcoming expectations and ideologies that accept and embrace cultural diversity. This acceptance of majority culture change, however, varies among welcoming attitudes, with some demanding more individual cultural change than others.

The results from the study also reveal that majority acculturation orientations can predict support for intergroup ideologies over time, with majority members’ acculturation strategies significantly impacting their expectations and ideologies. Interestingly, an integration or assimilation strategy for majority members could lead to either “surface” level cultural learning, where they adopt cultural elements without considering the consequences for minority groups, or deep cultural learning based on sharing power and regarding other cultures as equal. This highlights the importance of considering the nuances and complexities of majority acculturation in addressing societal challenges related to cultural diversity.

Do minority-group members embrace majority acculturation?

Majority acculturation has been criticized as possibly representing a form of cultural appropriation. Acculturation is commonly defined as a mutual accommodation process, while cultural appropriation refers to the use of a culture’s symbols, artifacts, genres, rituals, or technologies by members of another culture. The difference between the two is that cultural appropriation especially involves power dynamics and dominance, with the higher power group adopting and distorting the culture of other groups in a negatively perceived manner.

A new majority acculturation study by Kunst et al. (2023) aimed to understand the mutual acculturation expectations of Christian majority-group members and Muslim minority-group members in the U.K. and the relationship of these expectations to acculturation orientations and threat perceptions. Results indicated that Muslim minority-group members on average did not seem to disfavor the idea of majority-group members adopting minority-group culture.

Their acculturation expectations were not significantly related to perceptions of symbolic and realistic threats, which suggests that most Muslim minority-group members in the U.K. may not perceive majority-group acculturation as cultural appropriation in principle. However, they may be antagonistic toward how their culture is adopted in practice, which is a distinction that future research should explore.

The study also found that Muslim minority-group members who maintained their heritage culture endorsed the importance of cultural maintenance and adoption for all groups. Integrated minority-group members were relatively more supportive of majority-group members maintaining their culture but had neutral expectations regarding the adoption of minority-group culture. This counters the stereotype that immigrants, particularly Muslims, impose their culture on others.

While the findings may have implications for practitioners and policymakers, further research is needed to understand the conditions under which majority-group acculturation represents genuine and egalitarian change versus cultural appropriation. Intercultural encounters should show sensitivity toward the expectations of minority-group members to prevent cultural appropriation, but the research suggests that minority-group members may not generally reject the idea of majority-group members adopting the culture of minority-group members. Rather, they may endorse acculturation as a mutual cultural exchange.

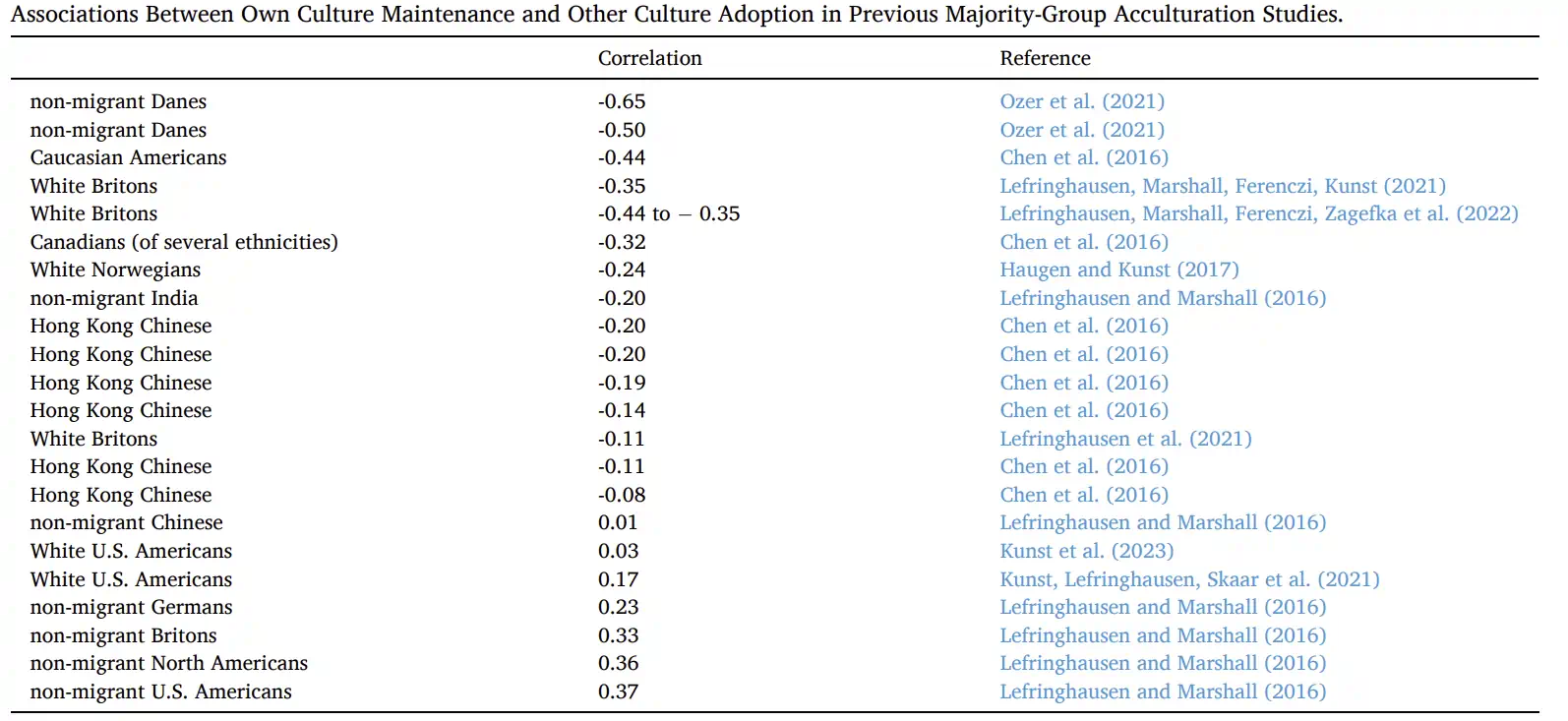

Across previous work, correlations between majority group acculturation orientations range from negative to positive, although most associations trend in the negative direction.

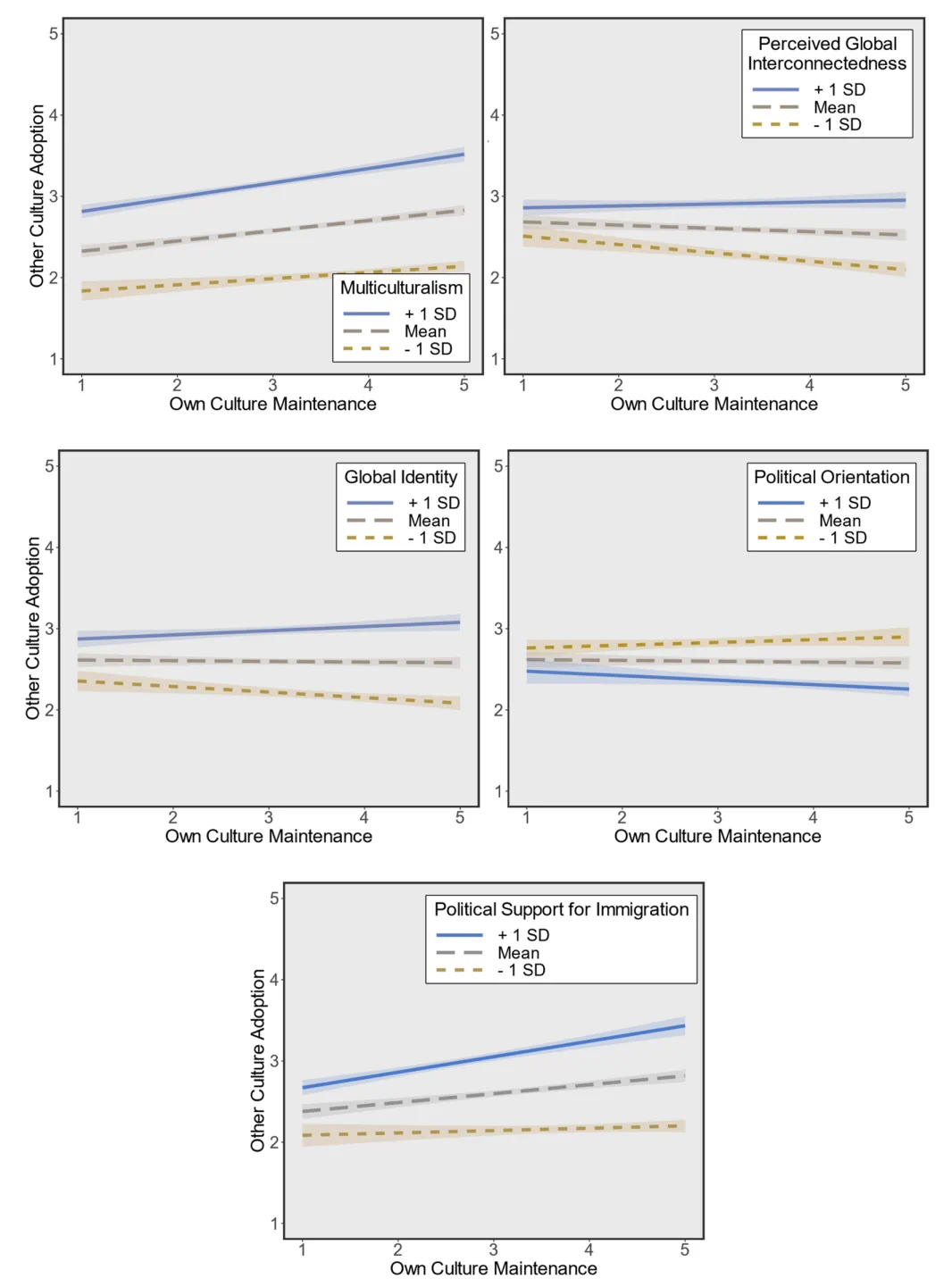

A recent study by Kunst et al. (2023) investigated factors that may determine the relationship between maintaining one’s own culture and adopting others among majority members, using a representative sample of 2,205 Germans. The study showed that factors such as multiculturalism, perceived interconnectedness, global identity, political orientation, and support for migration significantly influence the relationship between these majority acculturation orientations. Maintaining one’s own culture and adopting others was found to be positively associated at high levels of global identity and political support for migration, and the correlation increased with endorsement of multiculturalism. However, these orientations were negatively related at low to medium levels of perceived interconnectedness and global identity and among right-wing individuals. When all these factors were considered simultaneously, maintaining one’s own culture was positively related to higher levels of adopting others, particularly when regional identity was low or political support for immigration was high.

A recent study by Kunst et al. (2023) investigated factors that may determine the relationship between maintaining one’s own culture and adopting others among majority members, using a representative sample of 2,205 Germans. The study showed that factors such as multiculturalism, perceived interconnectedness, global identity, political orientation, and support for migration significantly influence the relationship between these majority acculturation orientations. Maintaining one’s own culture and adopting others was found to be positively associated at high levels of global identity and political support for migration, and the correlation increased with endorsement of multiculturalism. However, these orientations were negatively related at low to medium levels of perceived interconnectedness and global identity and among right-wing individuals. When all these factors were considered simultaneously, maintaining one’s own culture was positively related to higher levels of adopting others, particularly when regional identity was low or political support for immigration was high.

Is majority-group acculturation the same as cultural appropriation?

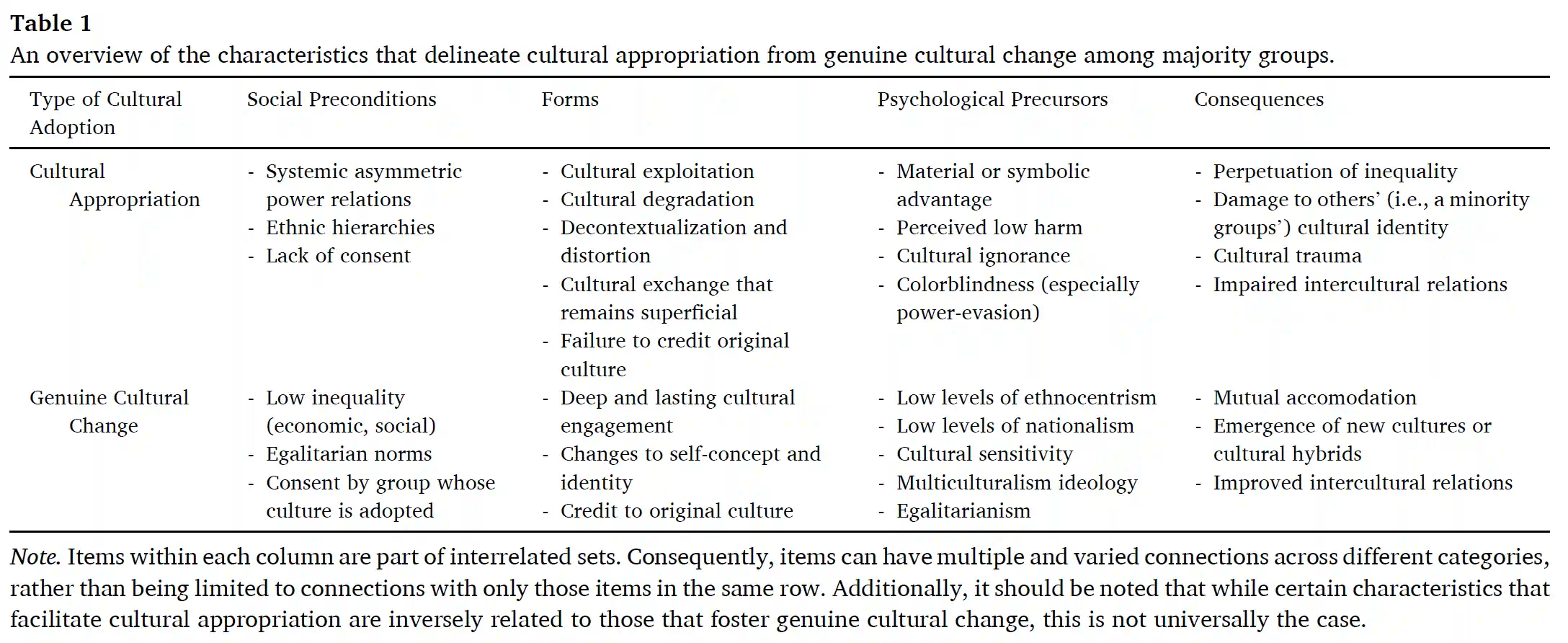

The question of whether majority-group acculturation is synonymous with cultural appropriation is a multifaceted and nuanced one, as highlighted in a recent theoretical article by Kunst et al. (2023). On one hand, cultural appropriation is often characterized by the use of elements from a less powerful group’s culture by members of a dominant group, lacking consent and often employed for personal gain, whether material or symbolic. This form of appropriation tends to occur without a deep understanding or respect for the original cultural context. It can result in the trivialization or commodification of significant cultural practices, symbols, or artifacts.

On the other hand, majority-group acculturation can also represent a genuine cultural change. This occurs when there is a respectful and deep engagement with the minority culture. Such genuine cultural change is marked by equality, mutual consent, and a commitment to understanding and preserving the integrity and significance of the cultural elements being adopted. It is a process of cultural exchange that is inclusive, reciprocal, and sensitive to the power dynamics and histories of both groups involved.

The distinction between cultural appropriation and genuine cultural change is crucial in understanding majority-group acculturation. While cultural appropriation is often viewed negatively due to its exploitative and superficial nature, genuine cultural change is a positive and enriching process, contributing to a more inclusive and diverse society. It fosters intercultural dialogue and understanding, allowing for a more dynamic and pluralistic cultural landscape.

However, the delineation between these two processes is not always clear-cut. The globalized context in which cultures interact today makes the boundaries ever more permeable and complex. Questions of cultural ownership and the rights to cultural elements become increasingly challenging to navigate. Therefore, the intent, manner of engagement, and the dynamics of power and consent play crucial roles in distinguishing between cultural appropriation and genuine cultural change. An overview of characteristics differentiating both can be found in the table below.

Relevant majority acculturation articles from our lab and collaborations:

Haugen, I., & Kunst, J. R. (2017). A two-way process? A qualitative and quantitative investigation of majority members’ acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 60, 67-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.07.004

Kunst, J. R., Lefringhausen, K., Sam, D. L., Berry, J. W., & Dovidio, J. F. (2021). The Missing Side of Acculturation: How Majority-Group Members Relate to Immigrant and Minority-Group Cultures. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(6), 485-494. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211040771

Kunst, J. R., Lefringhausen, K., Skaar, S., & Obaidi, M. (2021). Who adopts the culture of ethnic minority groups? A personality perspective on majority-group members’ acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 81 20-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.01.001

Kunst, J. R., Ozer, S., Lefringhausen, K., Bierwiaczonek, K., Obaidi, M., & Sam, D. L. (2023). How ‘should’ the majority group acculturate? Acculturation expectations and their correlates among minority- and majority-group members. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 93, 101779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101779

Lefringhausen, K., Marshall, T. C., Ferenczi, N., & Kunst, J. R. (2021). A new route towards more harmonious intergroup relationships in England? Majority members’ proximal-acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 82, 56-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.03.006

Lefringhausen, K., Marshall, T. C., Ferenczi, N., Zagefka, H., & Kunst, J. R. (2022). Majority members’ acculturation: How proximal-acculturation relates to expectations of immigrants and intergroup ideologies over time. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 0(0), 13684302221096324. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302221096324

Ozer, S., Kunst, J. R., & Schwartz, S. J. (2021). Investigating direct and indirect globalization-based acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 84, 155-167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.07.012

Kunst, J. R., Coenen, A.-C., Gundersen, A., & Obaidi, M. (2023). How are acculturation orientations associated among majority-group members? The moderating role of ideology and levels of identity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 96, 101857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101857

Dandy, J., Doidge, A., Lefringhausen, K., Kunst, J. R., & Kenin, A. (2023). How do Australian majority-group members acculturate? A person-centered approach. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 97, 101876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101876

Kunst, J. R., Lefringhausen, K., & Zagefka, H. (2024). Delineating the boundaries between genuine cultural change and cultural appropriation in majority-group acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 98, 101911. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101911

Recommended majority acculturation readings:

Lefringhausen, K., Ferenczi, N., & Marshall, T. C. (2020). Self-protection and growth as the motivational force behind majority group members’ cultural adaptation and discrimination: A parallel mediation model via intergroup contact and threat. International Journal of Psychology, 55(4), 532-542. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12620

Lefringhausen, K., & Marshall, T. C. (2016). Locals’ bidimensional acculturation model: Validation and associations with psychological and sociocultural adjustment outcomes. Cross-Cultural Research, 50(4), 356-392. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397116659048

Zagefka, H., Lefringhausen, K., López Rodríguez, L., Urbiola, A., Moftizadeh, N., & Vázquez, A. (2022). Blindspots in acculturation research: An agenda for studying majority culture change. European Review of Social Psychology, 1-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2022.2079813

R’boul, H., Dervin, F., & Saidi, B. (2023). South-South acculturation: Majority-group students’ relation to Sub-Saharan students in Moroccan universities. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 96, 101834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101834

Ozer, S., & Kamran, M. A. (2023). Majority acculturation through globalization: The importance of life skills in navigating the cultural pluralism of globalization. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 96, 101832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101832

Hang, Y., & Zhang, X. (2023). Acculturation and enculturation of the majority group across domains. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 97, 101893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101893

Vázquez-Flores, E., López-Rodríguez, L., Navas, M., & Boughaba, F. (2023). Getting closer to the minority culture: Experimental evidence of cultural enrichment to increase attributions of morality and majority adoption of Moroccan cultural patterns. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 96, 101864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101864

Egitim, S., & Akaliyski, P. (2023). Intercultural experience facilitates majority-group acculturation through ethnocultural empathy: Evidence from a mixed-methods investigation in Japan. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 98, 101908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101908

Amenabar-Larrañaga, L., Arnoso-Martínez, M., Rupar, M., & Bobowik, M. (2023). Narratives of linguistic victimhood and majority groups’ acculturation strategies and multilingual attitudes: The mediating role of intergroup empathy. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 97, 101906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101906

Jasini, A., Tekin, E. A., Vieira, F. F., & Mesquita, B. (2024). Majorities’ emotions acculturate too: The role of intergroup friendships and clarity of minority emotion norms. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 98, 101923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101923

Scales to measure majority acculturation

The following scales have been validated and can be used freely to measure majority acculturation. You may measure majority acculturation with regards to the culture of immigrants generally or specific immigrant groups (feel free to adjust the scales to your needs, societies, and contexts).

Majority Acculturation and Expectations Scales (Kunst et al. 2023)

The following scales can be used to assess both the acculturation of majority and minority groups in comparative research including the expectations of each group. They build on the scale by Huagen & Kunst shown below, but represent a more refined version. Please note that the contact item sometimes does not load with the other items and may need to be omitted. The reference to the scale is as follows:

Kunst, J. R., Ozer, S., Lefringhausen, K., Bierwiaczonek, K., Obaidi, M., & Sam, D. L. (2023). How ‘should’ the majority group acculturate? Acculturation expectations and their correlates among minority- and majority-group members. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 93, 101779. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101779

All items are rated on 7-point scales ranging from “Not important at all” to “Very important”

For majority groups:

Own culture maintenance

The following questions deal with how important it is for you to relate to your ethnic heritage culture and the mainstream culture.

- How important is it for you to maintain the mainstream British cultural way of living?

- How important is it for you to maintain mainstream British traditions?

- How important is it for you to maintain mainstream British values?

- How important is it for you to maintain the mainstream British culture in your life?

- How important is it for you to feel that you belong to the mainstream British culture?

- How important is it for you to have contact with other White British people?

Other Culture Adoption

- How important is it for you to participate in immigrants’ and minority groups’ cultural way of living?

- How important is it for you to participate in the traditions of immigrants and minority groups?

- How important is it for you to live in accordance with the values of immigrants and minority groups?

- How important is the culture of immigrants and minority groups in your life?

- How important is it for you to feel connected to the culture of immigrants and minority groups?

- How important is it for you to have contact with immigrants and minority groups?

Other Culture Adoption Expectations

Some believe that only immigrants or minority-group members have to adapt to the culture of the majority group. Others believe that majority-group members also need to adapt to the culture of immigrants and minority-group members. The following questions deal with how important you think it is that majority-group members maintain their culture or adopt to the culture of immigrants and minority groups.

- How important is it that immigrants and minority-group members adopt the mainstream British cultural way of living?

- How important is it that immigrants and minority-group members adopt mainstream British traditions?

- How important is it that immigrants and minority-group members adopt mainstream British values?

- How important is it that immigrants and minority-group members adopt the mainstream British culture in their lives?

- How important is it that immigrants and minority-group members feel belonging with the mainstream British culture?

- How important is it that immigrants and minority-group members have contact with White British people?

Culture Maintenance Expectations

- How important is it that immigrants and minority-group members maintain their ethnic cultural way of living?

- How important is it that immigrants and minority-group members maintain their ethnic traditions?

- How important is it that immigrants and minority-group members maintain the values of their ethnic heritage group?

- How important is it that immigrants and minority-group members maintain their ethnic culture in their lives?

- How important is it that immigrants and minority-group members feel belonging with the culture of their ethnic heritage group?

- How important is it that immigrants and minority-group members have contact with other members of their ethnic groups?

For minority groups:

Other Culture Adoption

The following questions deal with how important it is for you to relate to your ethnic heritage culture and the mainstream culture.

- How important is it for you to adopt the mainstream British cultural way of living?

- How important is it for you to adopt mainstream British traditions?

- How important is it for you to adopt mainstream British values?

- How important is it for you to adopt the mainstream British culture in your life?

- How important is it for you to feel that you belong to the mainstream British culture?

- How important is it for you to have contact with White British people?

Own Culture Maintenance

- How important is it for you to maintain the cultural way of living of your ethnic heritage group?

- How important is it for you to maintain the traditions of your ethnic heritage group?

- How important is it for you to maintain the values of your ethnic heritage group?

- How important is the culture of your ethnic heritage group in your life?

- How important is it for you to feel connected to the culture of your ethnic heritage group?

- How important is it for you to have contact with members of your ethnic heritage group?

Cultural Maintenance Expectations

Some believe that only immigrants or minority-group members have to adapt to the culture of the majority group. Others believe that majority-group members also need to adapt to the culture of immigrants and minority-group members. The following questions deal with how important you think it is that majority-group members maintain their culture or adopt to the culture of immigrants and minority groups.

- How important is it that White Britons maintain their mainstream British cultural way of living?

- How important is it that White Britons maintain their mainstream British traditions?

- How important is it that White Britons maintain their mainstream British values?

- How important is it that White Britons maintain the mainstream British culture in their lives?

- How important is it that White Britons feel belonging with the mainstream British culture?

- How important is it that White Britons have contact with other White British people?

Other Culture Adoption Expectations

- How important is it that White Britons adopt the cultural way of living of immigrants and minority groups?

- How important is it that White Britons adopt the traditions of immigrants and minority groups?

- How important is it that White Britons adopt the values of immigrants and minority groups?

- How important is it that White Britons adopt the culture of immigrants and minority groups in their lives?

- How important is it that White Britons feel belonging with the culture of immigrants and minority groups?

- How important is it that White Britons have contact with immigrants and minority groups?

Majority Acculturation Index (Haugen & Kunst, 2017)

The reference to this majority acculturation scale is as follows:

Haugen, I., & Kunst, J. R. (2017). A two-way process? A qualitative and quantitative investigation of majority members’ acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 60, 67-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.07.004

Responses are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from “not important at all” to “very important”.

- How important is it for you to have contact with people with an immigrant background?

- How important is it for you to have contact with ethnic Norwegian

- How important is it for you to adopt the cultural way of life of immigrants?

- How important is it for you to maintain the Norwegian cultural way of life?

- How big a part of your life is the culture of people with an immigrant background?

- How big a part of your life is Norwegian culture?

- How important is it for you to live according to the values of immigrant cultures?

- How important is it for you to live according to Norwegian values?

- How important is it for you to follow the traditions of immigrant cultures?

- How important is it for you to uphold the traditions of Norwegian culture?

- How important is it for you to feel you belong in immigrant cultures?

- How important is it for you to feel you belong in Norwegian culture?

- How important is it for you to adopt the view on gender roles found in immigrant cultures?

- How important is it for you to uphold the Norwegian view of gender roles?

Multi-Vancouver Index of Acculturation (Lefringhausen et al. 2016)

The reference for this majority acculturation scale is:

Lefringhausen, K., & Marshall, T. C. (2016). Locals’ bidimensional acculturation model: Validation and associations with psychological and sociocultural adjustment outcomes. Cross-Cultural Research, 50(4), 356-392. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397116659048

Responses are scored from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”.

- I often participate in my American cultural traditions.

- I would be willing to marry a person from my American culture.

- I enjoy social activities with people from my American culture.

- I am comfortable working with people of my American culture.

- I enjoy entertainment (e.g., movies, music) from my American culture.

- I often behave in ways that are typical of my American culture.

- It is important for me to maintain or develop the practices of my American culture.

- I believe in the values of my American culture.

- I enjoy the jokes and humor of my American culture.

- I am interested in having friends from my American culture.

- I often participate in diverse cultural traditions.

- I would be willing to marry a person from a diverse culture.

- I enjoy social activities with people from diverse cultures.

- I am comfortable working with people from diverse cultures.

- I enjoy entertainment (e.g., movies, music) from diverse cultures.

- I often behave in ways that are typical of diverse cultures.

- It is important for me to maintain or develop the practices of diverse cultures.

- I believe in diverse cultural values.

- I enjoy jokes and humor of diverse cultures.

- I am interested in having friends from diverse cultures.

What are the consequences of majority acculturation?

What are the consequences of majority acculturation?